A multi-award-winning printing house, Plus Print are known for their expertise and passion for print. Embracing the latest technologies and with great respect for their practice, they create outstanding results for a range of clients from the corporate to the arts and culture world.

Inside knowledge can be some of the most invaluable. With this in mind we have conducted interviews with some of the most renowned publishers in the business today. These insights serve to contextualise the Blow Photobook Programme and provide an overview of the entailed process for applicants.

©

©

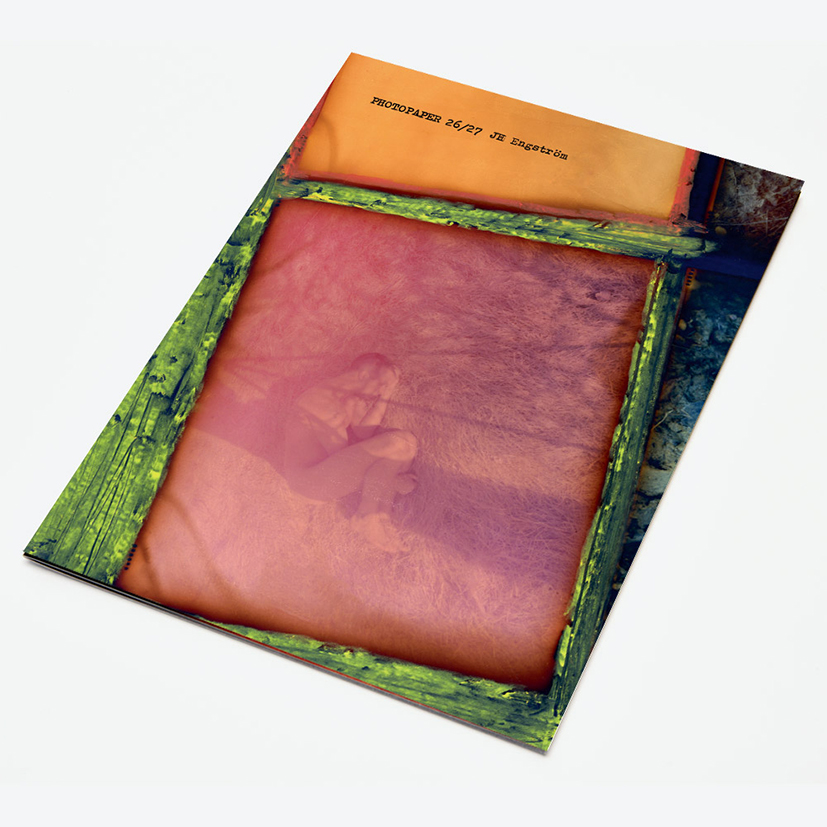

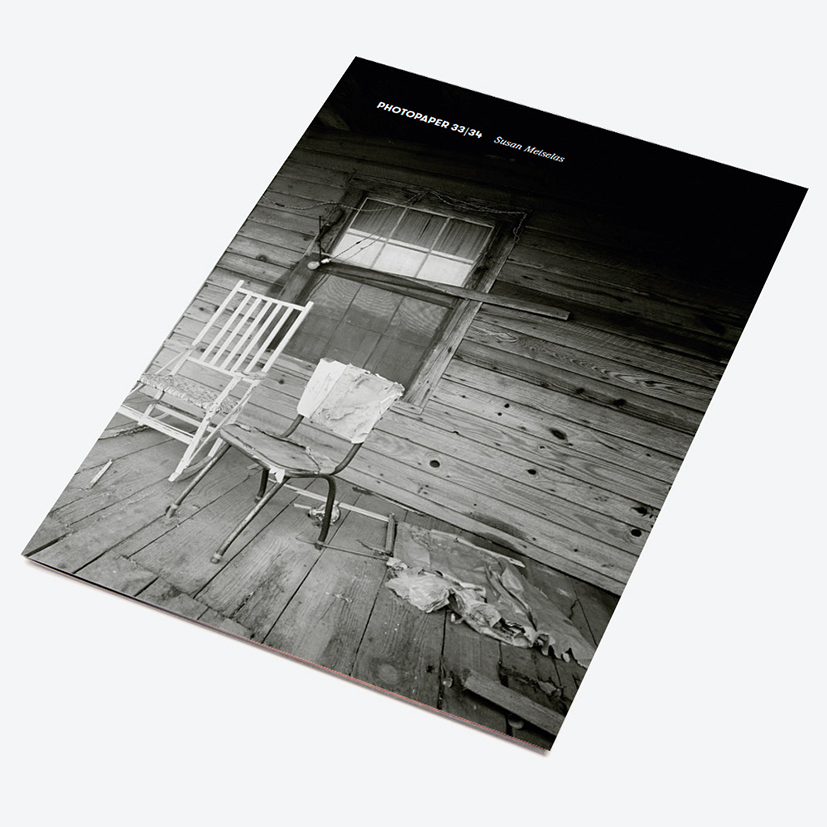

Dieter Neubert is the founder and director of the Kassel Fotobookfestival, the founder of the Kassel Photobook and Dummy Awards and the chief editor of the monographic magazine “Photopaper”. He edited and published several books, like the Daido Moriyama anthology “On Daido”, Martin Parr’s artist book “Kassel Menu” and some volumes of the annual catalog “Best Photobooks”.

HERE IS HOW IT STARTED

I began to look at photobooks and special photo art magazines during my studies in the Eigthies at the Kunsthochschule Kassel. Floris M.Neusüss was teaching photography in Kassel at that time and he built up a fantastic collection of photobooks for the Kunsthochschule library. You can find all the classics there. That was the only way to get in touch with what was going on in photography.

There was something in the air about photobooks. We had a small photofestival in Kassel and in 2008 we thought we should place the theme of “Photobooks” at the centre of it. I invited some experts, like Martin Parr, John Gossage, Cuny Jansen, Pablo Monasterio and Markus Schaden, to spend a long weekend looking at and speaking about photobooks. That was a fantastic experience and had a great response worldwide. So a new kind of festival was born.

As a publisher, my first project was “On Daido”, an anthology and homage to one of the greatest photographers ever. We invited Daido Moriyama to come to Kassel in 2013 and dedicated the whole festival to him. For “On Daido”, I invited photographers, critics, writers and curators to give a personal comment on Daido Moriyama. At the end we had a fantastic compilation of many extraordinary photographic and literally statements. We used crowd-funding and a sponsor to finance it.

Jacob Aue Sobol

THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE

The biggest challenge is boring: to finance everything and to get enough public response and support from official cultural institutions. But in the end you have to find your own way of getting everything together. Like the book “On Daido” and two years later the artist book “Kassel Menu” I did with Martin Parr. The sales from those books helped to finance the festival.

HOW THE DUMMIES GET SELECTED FOR THE FESTIVAL?

Every photographer can enter books. There is no restriction, except that the dummy may not have already been published by a publishing house. The first selection is made by a Shortlist Jury. This jury selects 50 books which will go on an international exhibition tour to festivals, libraries, and institutions. This jury changes every year and it is a good mixture of women, men, photographers, publishers and curators, who are all very familiar with the medium of the photobook. The Final Jury then selects 3 winning books. Both juries have 6-8 members.

WHAT IS YOUR PUBLISHING PROCESS?

Over the last few years I started a new publishing project called PHOTOPAPER. It’s a new kind of monographic photo publication with a continuously changing editorial team. This publication features interesting work in single monographic issues. The main idea is to make high-quality printed photographic work accessible to as many people as possible by producing the final publication at a reasonable price. Therefore, the production process is reduced to a minimum, while at the same time using high-end printing technology and nice paper. So starting a new issue is a bit like working on a dummy: selecting images, editing, sequencing etc. Sometimes we produce physical dummies, sometimes we work only digitally until the printed issue. I take it from the beginning to the end, and work together with an editor, designer and printer.

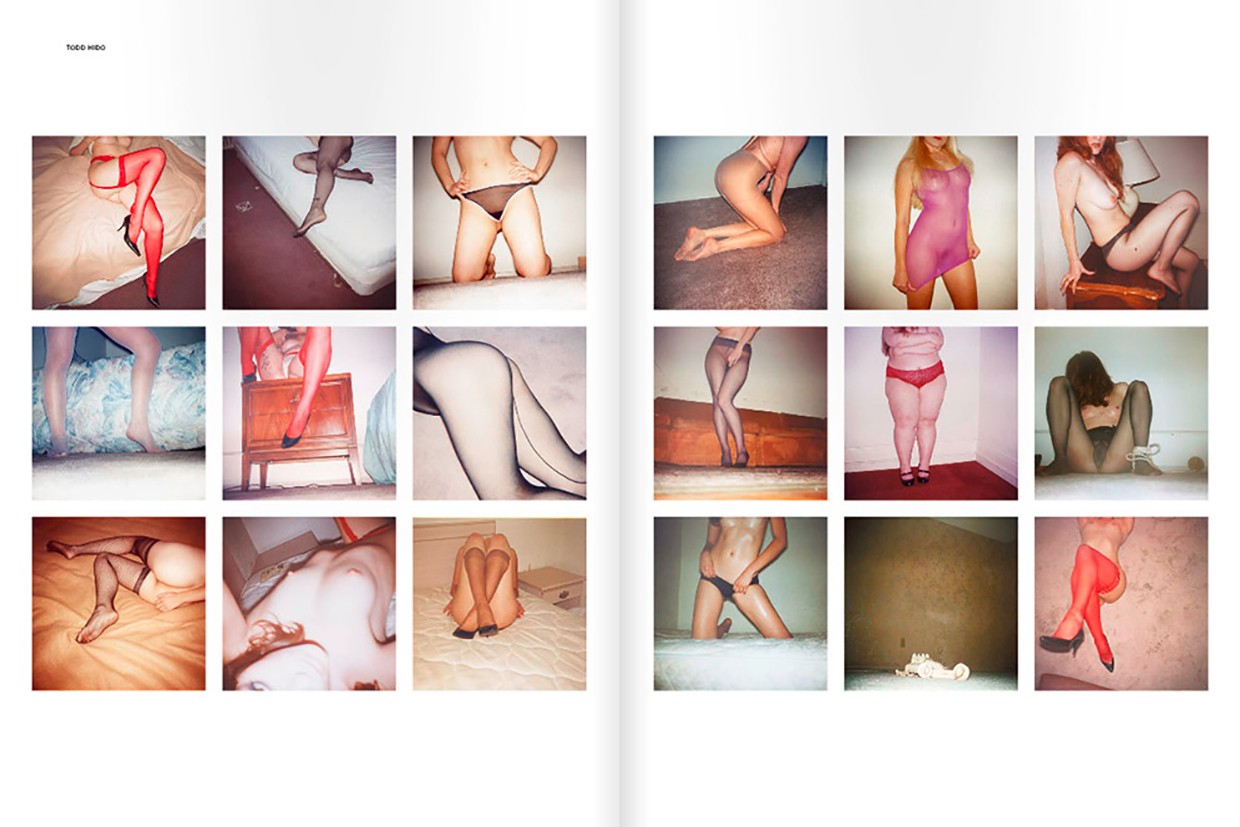

Todd Hiddo

ADVICES ON DUMMIES

Sometimes photographers try to make a formally perfect book. These books look as if they have been published already. But a dummy is not supposed to be perfect.

The main goal is a unique idea and a matching unique photographic language. Don’t use text if you are not sure if you can handle this on the same level as your photography, dont try to explain too much, try to work together with an editor and/or designer a.s.o.

DO YOU ALWAYS USE THE SAME DESIGNER? THE SAME PRINTER?

For most projects I work together with the same designer, the printers change. It depends on the project: for some publications a specific printer is the right choice because of the equipment he is using and because of his experience with this specific technique.

HOW DO YOU CHALLENGE YOUR PERCEPTION AND THE WAY YOU JUDGE THE DUMMIES FOR THE FESTIVAL?

Getting a program together is a long process of finding core aspects and the right mix of well-known photographers and unknown talents. But in the end, I never make the selection alone but together with people I trust and know have experience in photography.

MY DISTINGUISHING FEATURE AS A PUBLISHER

Photo books today are not accessible to many people around the world. One reason for this is because they are expensive. The democratic nature of books is that they can be read by many people. So we try to reach this goal by publishing “Photopaper’’. Maybe that’s the difference.

AN ADVICE TO THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO WANTS TO PUBLISH HIS / HER FIRST BOOK

A good way is to participate in Dummy Awards. Awards which show the essence of the submitted books in travelling exhibitions that can reach many interested and important people, like publishers, jurors and curators – that’s a great way to spread ideas in book form.

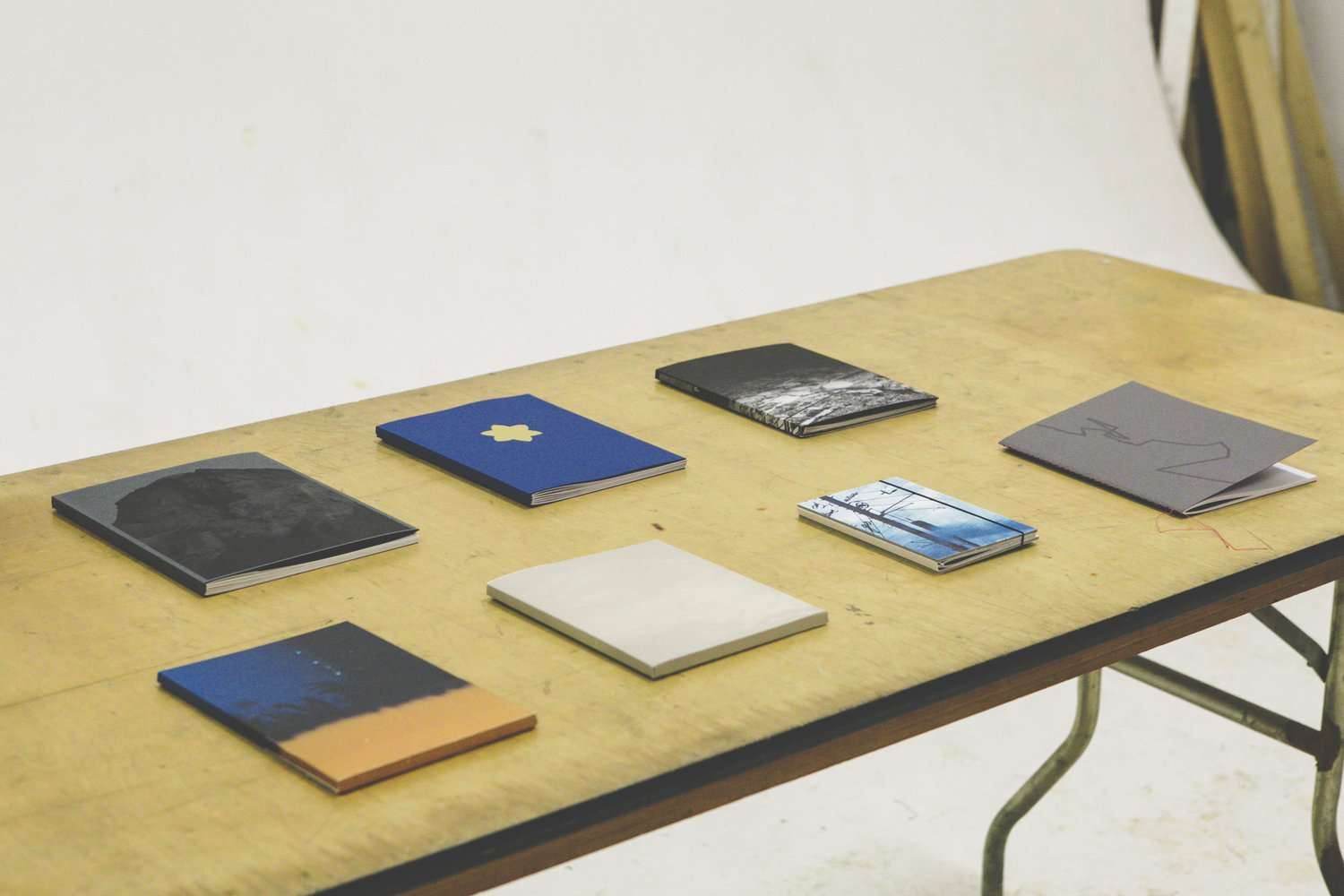

2016 Beijing Dummy

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

©

©

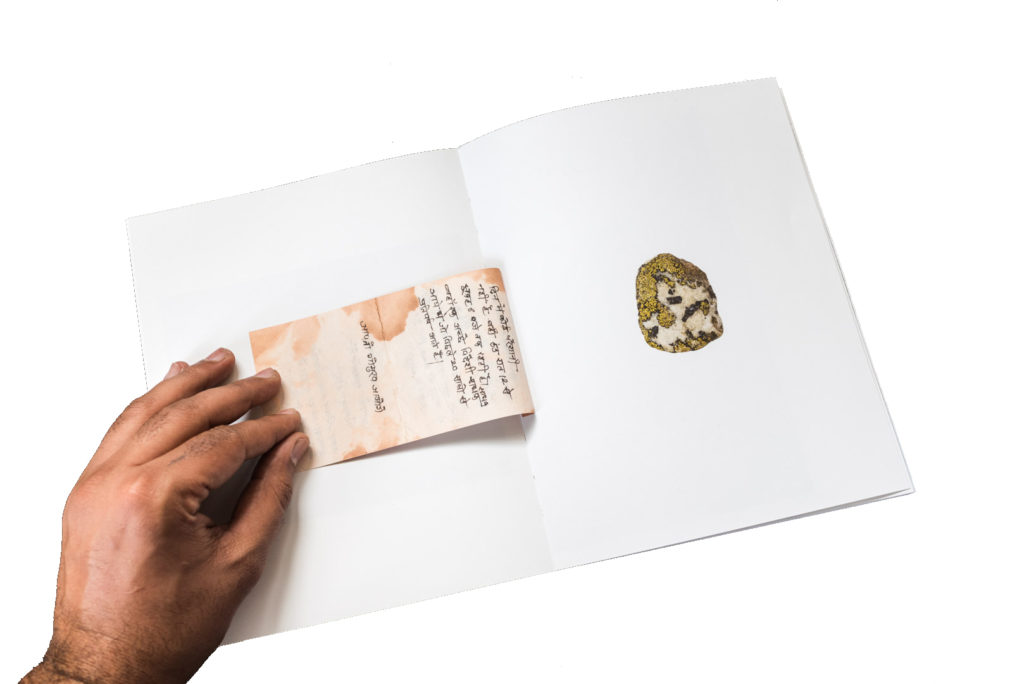

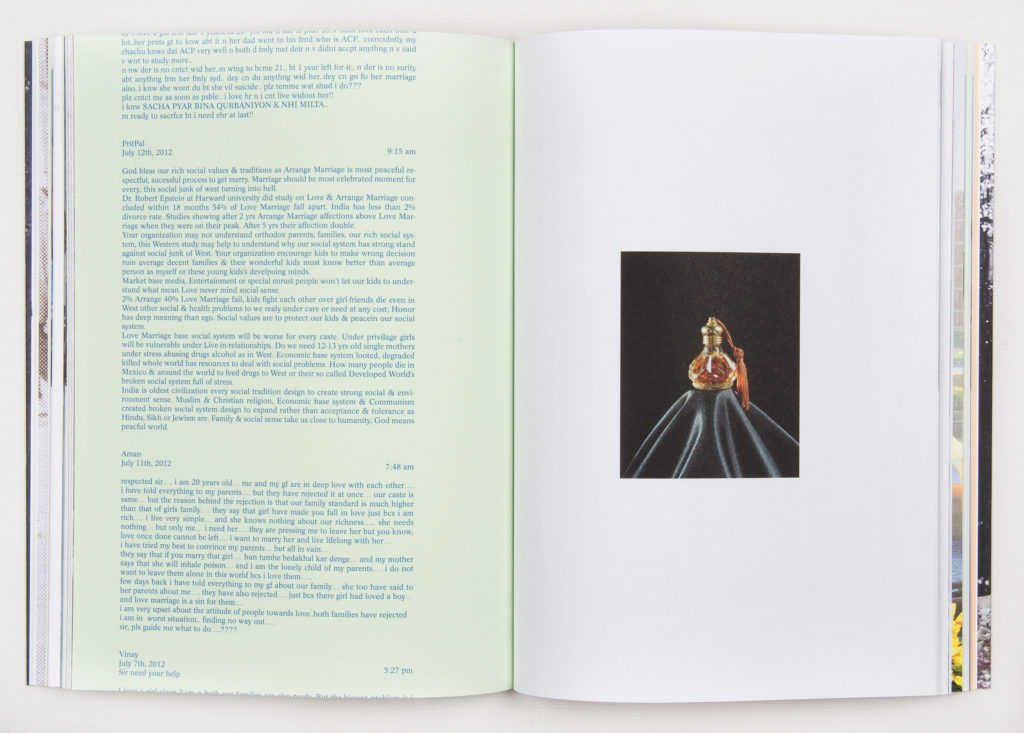

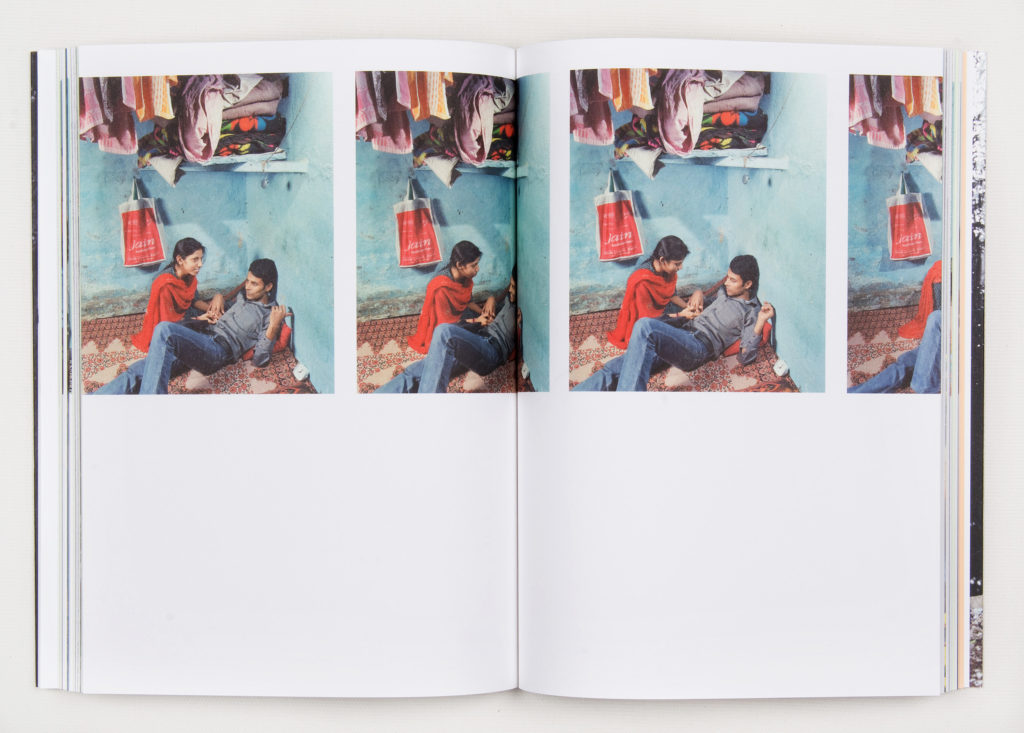

Nishant Shukla is a visual artist and photographer based between London & India. His personal body of work addresses questions of identity, origins and essence through an exploration of the margin; peripheral moments, spaces and people that are commemorated with images and objects that intersect with his own journey.

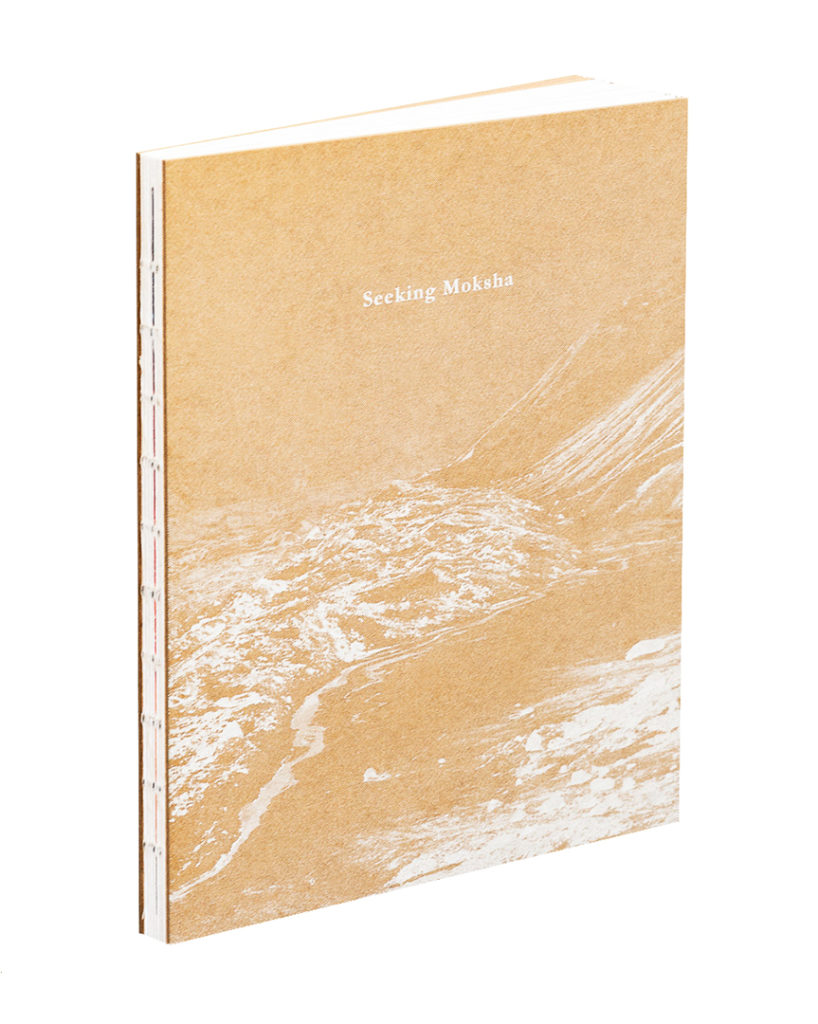

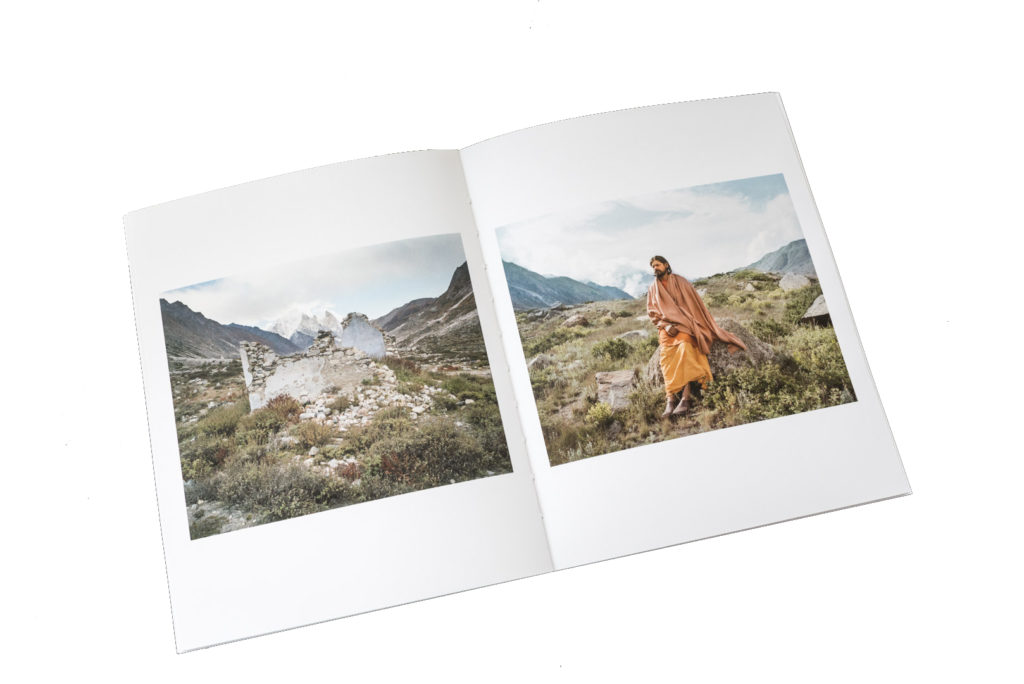

In 2015, with with Philippe Calia, Andrea Fernandes, Asmita Parelkar, and Sunil Thakkar, he co founded BIND which is a platform for contemporary photography centered around a photobook library in Bombay. Shukla self published “Seeking Moksha” in 2016, a personal journey and search for transcendence entangled with people he encountered on a pilgrimage to collect water for his grandfather.

https://www.nishantshukla.com

https://bindcollective.in

HERE IS HOW IT STARTED

In 2014 I co-founded a platform for photo books called BIND in Mumbai with some friends, which currently exists as a photobook library. This really got us deeply involved with photobooks. Around the same time I wanted to make a small number of handmade books for a long term personal project called Seeking Moksha, so I made a dummy and then applied for a grant and subsequently to a few more grants.

FIRST BOOK FINANCING

I was fortunate to be awarded the Alkazi Foundation : Photobook Grant in 2016 which partly funded the production of the book.

THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE

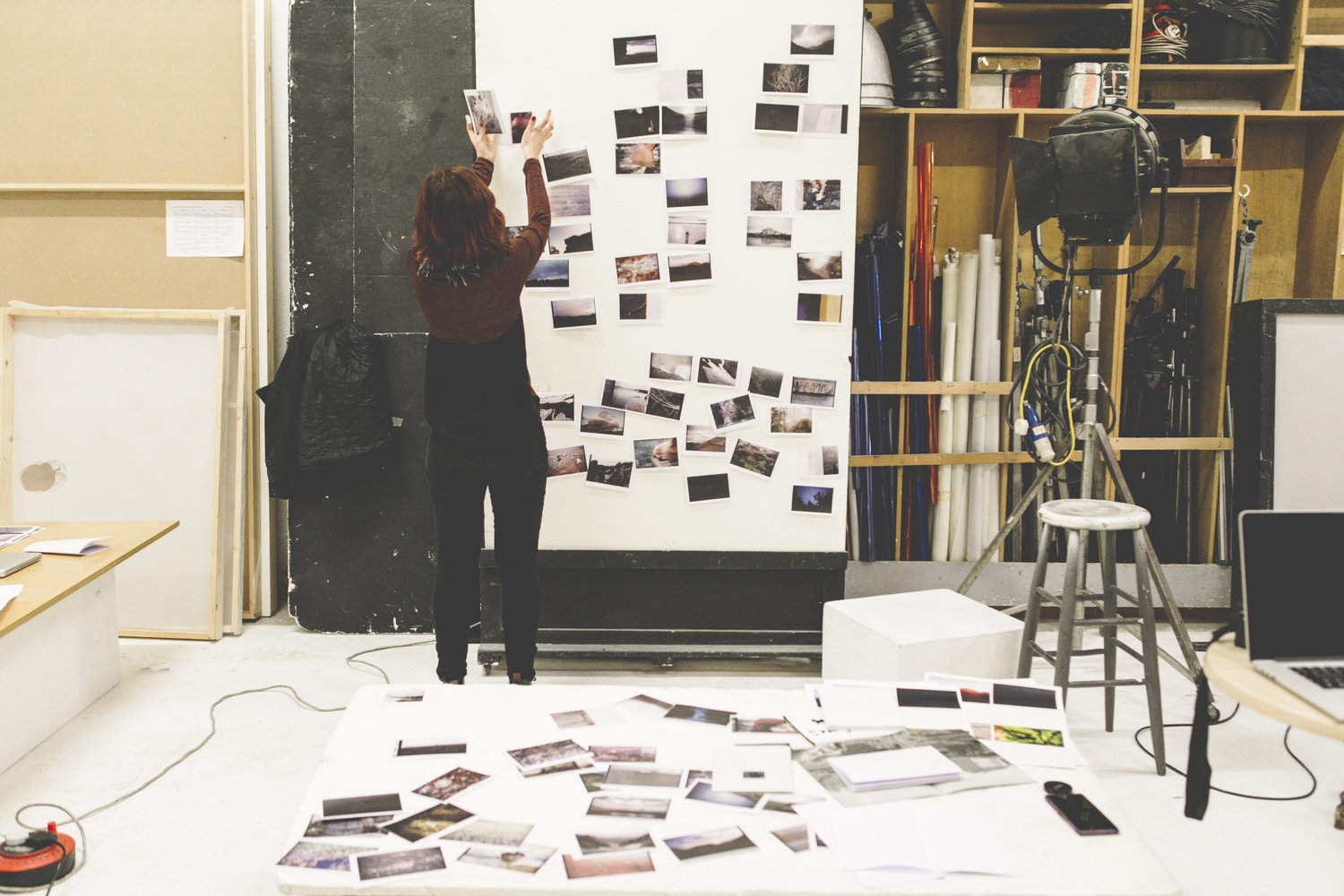

It has to be sequencing. There are so many different ways to sequence the same work. Every photographer will take a different route. Finding that voice and understanding how to build a sequence of images that tell to a compelling story takes time. I had at least 30 different versions and I would stare at it on my wall and rearrange over a period of 5 months. The last 5 versions were all good books. Knowing when to stop is also hard.

HOW DO YOU SELECT A BOOK FOR THE LIBRARY

In context of the library that we run through BIND, we initially started with our own personal collections of photo books along with donations that we received through open calls we put out for projects that we were curating. Now we largely only request books that we are going to include in an upcoming curation or very selectively add to the library.

DUMMY

I don’t really see the production quality as an issue with the dummy as long as it can communicate the idea. I really love to see dummies of books because it really shows you the author’s vision before other people have got involved.

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, HOW DO YOU WORK ON YOUR DUMMY?

I started the process alone and found it really difficult to edit & sequence my work. I asked for some help from some people I trusted about edit & eventually the book was co-edited.

I designed my first dummy myself but after receiving the grant I collaborated on the design with a book designer.

Your impact on the final shape of the book depends on who you end up working with. There are publishers who really like to stay true to the artist’s vision, while others prefer to be involved in conceptualisation. Even if you choose self-publishing route, you have voices that guide the book in different directions for a variety of different reasons from availability of materials to production capabilities.

INGREDIENTS OF A SUCCESSFUL BOOK

As long as you are happy with the final book and feel that it was worth chopping of the trees involved than I feel the book is a success. But the public image of success is surely helped when the book is shortlisted for or wins awards.

WHAT TO THINK ABOUT SELF PUBLISHING

I love the idea of having complete control over the making of your own book. I tend to feel more precious about books that are made by one person compared to by larger publishers.

Having said that, self-publishing isn’t for everyone. I was really passionate about printing methods and was happy to experiment. But I didn’t anticipate how much work distribution was going to be, for instance.

AN ADVICE TO THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO WANTS TO PUBLISH HIS FIRST BOOK

There are no rules but, personally:

Make a list of all the dummy awards that interest you and print that many dummies & apply. It really helps to do this process.

If you don’t get an award or a publisher, then make a small batch of handmade books or do a small print run and move onto the next project.

I would avoid publishers who charge you to print your book unless of course you have stacks of cash at home.

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

© Andrea Copetti by Colin Pantall

© Andrea Copetti by Colin Pantall

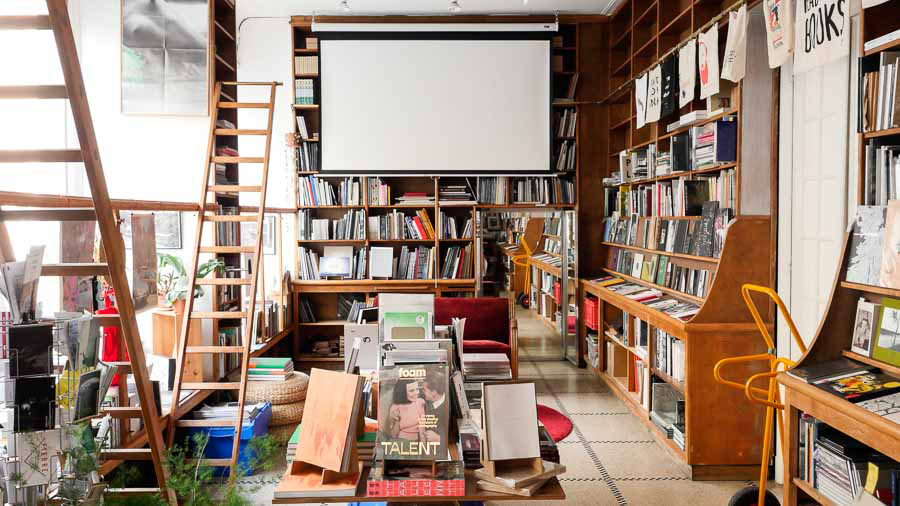

Andrea Copetti is the owner of The Tipi Photo Bookshop, an independent bookshop based in Brussels. Established in 2012, the space is dedicated to small publishers and self-published photo books.

HERE IS HOW IT STARTED

Everything started in a rather noble way, at the end of my photography studies. My teacher, Gilbert Fastenaekens, liked my way to see pictures, related to other pictures, rather than focusing on an exhibition like the other students. So he left me his publishing house, ARP editions. Like Obelix [a famous 1960s comic book hero], I was pushed into the cauldron. I ran ARP on a voluntary basis for five years, while working as a framer and doing other jobs. Eight years ago, I quit the publishing house, because there was not enough guts, not enough narrative or graphic ambition.

At a time when everyone said the paper is dead, the only idea that came to me was to start a bookshop. It took me two years.

Someone introduced me to someone who was selling his space. Lots of potential, because in a street mainly with single-family homes, not a hyped area, with no other cultural centres, it was an island. Perfect. I put all my savings in it and it took me a year and a half to renovate.

The bookshop started with my own collection of books that I bought when I was a student: two linear meters running 40m2 on the ground and 3.70m high, so not much.

The idea was doubly utopian: to sell my own books that I really loved, wishing that in a year or two, I’d be able to buy them back on internet or in a bookstore. That’s what happened. People put their confidence in the project, not that of a subsidised person, or an institution, but just of a photographer who was selling the books of other photographers, who saw the books with photographs not as they would cookies or other items sold at a checkout. So it is thanks to the community that the project was born.

Two meters running have become four meters. I put forward self-published books because I did not want to enter the distribution system of other bookstores: a system that’s all about standardisation of choice. In all major bookstores in Paris or Brussels, the same three big distributors flood the market with the same titles. And so I told myself there is no point in opening a bookstore that presents the same things that a bookstore in the city centre does. So I seek and seek all the time, in Belgium and abroad. I started to run fairs, to bring in books of photographers or authors who cannot move—because it is a fragile market, when you sell a book you do not earn a lot of money.

TELL US ABOUT YOUR APPROACH TO SELECTING BOOKS

Trust is created in a disembodied way, you send an email to someone who has put all his savings in his book. You tell him: ‘here you must trust me, send me your books, I won’t take them on deposit, but will do my best to sell them.’ Every time we buy books, we take a risk. It’s inevitable. The photographer realises this, and that in fact there is a human relationship created, an artistic relationship, a long-term relationship. It doesn’t take just a week; the discussions can last three to six months. Then I have to think about how to talk about the book, often there are books nobody has written about. How to find the words to transmit to people who are in my neighbourhood, or on internet, to make them understand that this author’s book, that we have never heard of, is interesting.

I like to put very complex books in the hands of people to see their reactions so that after, when I send an email to the author, I tell him ‘these people reacted like this to your book.’

Carmen Winant’s book My Birth for example, is very interesting, because we see deliveries: her delivery, that of her mother and the women she found on the internet. And we see how a young generation of photographers reacts to that, how older ladies or men react to that. It’s very rich for the author, but also for me—to not know an audience but be able to put stories on a taboo or intimate subject into their hands.

WHY DO YOU AVOID JUMPING ON THE BANDWAGON TO STOCK THE LATEST BIG THING?

For me a book has no age, it can be still interesting in six years. In large bookstores, it is a perishable object, because they impose a return on the distributor. The deal is that you get 30,000 books a year, but you have the right to send back 25,000. That means that when people find that there are a lot of photo books published every year, that’s true, but it’s a lure. All the books you see on the shelves of some bookstores that change every week are only because the libraries do not take them, they take them in stock and send them back. That’s why many booksellers say they’re just doing cartons.

I do the opposite work. I believe that it is micro stories that speak in the long run. It’s a curatorial job over time. I have books that are there from the beginning of the bookstore, which I think are important, so I will not send an email to the artist to ask him to buy me the books back because I want to make room. It’s a commitment to another type of culture promotion.

ANY ADVICE TO PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO WANT TO PUBLISH A BOOK?

It is necessary to try not to compromise too much on the basic idea. Then, we must understand that the basic idea will have to enter a new geography. This is not a geography of the exhibition, or the hard drive, things you see on display on your screen. We have to see how far we can go, how much creative freedom we can take; and how far we must not go. An object we want to put into hands but is impossible to handle, a book we can’t get into, can’t understand. Books like this may be interesting from the point of view of research, but if you want to make a certain run of edition, will people understand? Are we going to be a little too haughty from the point of view of form and concept?

Of course it can be a choice, an attitude to only address a niche audience, but that attitude is not mine. If do not understand it, I will not be able to explain it. Every week, someone comes in and asks me to explain a book, and I can’t reduce it to a series of images with keywords, it’s not enough for me. I am sure that the more we educate people to demand more from a story, the more the more the author will demand of himself. What matters is integrity and requirement. And in between, plenty of essentials to consider, like accessibility in terms of history, and how one can convey the story.

WHAT ABOUT A BOOK MOVES YOU TO TAKE IT?

I have real surprises. Every summer in Arles and other festivals, there is someone I do not know who comes with his story that I do not know and I cry! It may sound very naive, but when the person gets true, naked, you can’t treat her as a customer, but a human being. It’s just how the person presents the work, how it represents his or her convictions, its relation to his or her journey. You have to be very aware of yourself, to your feelings about a job, and if something emerges from that, let it emerge, it has to come out. But it’s not because a job moves me that [I take it], it can be a very good job and a very bad dummy—there are still a lot of steps.

And as much as I can be moved, I can be very angry at some publishers who edit very badly, who print badly. It annoys me when publishers print too fast because they think that there is a demand and that this demand must be fulfilled. There is also [the pressure of] a distribution chain that asks you to send the titles of the books three to six months in advance and so the publisher says to the artist, ‘We have to be quick now and print this book,’ and the author says, ‘Ok, you’re sure?” And the publisher says, “Yes, yes, yes I am sure.”

Sometimes there are choices that must be slower; graphic designers, publishers, who take a year or two before finishing a book, and that’s normal. I’m sometimes shown dummies almost finished, but it’s not perfect, I tell the photographer ‘You give them ammunition’ because I do not want people to end up like this.

So the requirement is not from the commercial point of view. Of course there is a business, they pay €3,000 or €8,000 to print the book, but if the book is good, no matter the price of production, it will sell, people will come with their money. The first notion is that the work must be right.

WHAT DO FAIRS AND FESTIVALS CONTRIBUTE TO THE CULTURE?

There’s difference between a festival and a fair, Paris Photo is a fair, they are here to sell. A festival is more focused on research. At Unseen you will see forms not saleable, not directly marketable. There is a lot of hypocrisy in Paris Photo. People who say that the photo book market is in crisis, maybe because they can’t renew their vocabulary around a work, they can’t get a work out of the boundaries of a frame, and out of this frame there is a gallery. They can’t do it because they are merchants and there are too many merchants and not enough artists who talk about their own works, and that’s why there’s this revolution of self-publishing, artistic revolution, and not commercial, but one leads to the other anyway. When we are facing the author, he reveals information to you about the work, about some characters. A gallerist can’t tell you that because it is not his job, because in fact he is a merchant and disillusioned because he never sells enough.

IS THE BUSINESS IN CRISIS?

Booksellers say that the book is in crisis, and, you know why? Because you have the same books as your colleague in the same city. What if you have other books with more complicated titles and that you defend them, on the social networks or in your bookstore? If somebody enters and tell you that he’s interested in architecture, yes very well, I will show you a photographer who works for example on places of conflict, architecture seen in places of conflict. Either you show him the catalog raisonné de le Corbusier, or you show him a new author who can shift his relationship to his notion of architecture: ruins in relation to the reconstruction in Palmyra, or in a country he only hears about in the news.

I do not put a book on my table in a festival if I do not understand it. I quote this example of an Iranian artist who has worked on her own story. She had chemo and after that she had a hysterectomy. How does a man, a publisher, a bookstore owner explain this? I may have had a vasectomy, but I am not female and have never experienced such damage to my body. I can explain the elements of the book and that there are human elements. But how do we adapt our speech to the person in front of you, who holds the book you’ve just explained and tells you ‘Yes I know what a hysterectomy is, I had one.’ Ok. We move to the next level. And so that’s what’s exciting. By renewing one’s vocabulary with each book, with each author, understanding it, you can speak differently each time, it should even be an exercise. I’m building a workshop room behind the bookstore for that: I ask you to explain your work in four different ways, it’s not a business pitch to sell something, it’s to see how we can explain a work from several points of view, as with multiple cameras, and it is essential.

Sometimes I get quite angry that people do not explain the work. I’m not a politician, I’m not one who’s used to talking in front of people, but I’m used to people I do not know asking me to explain a work. I will not just say it’s a new book, or it has received two awards. It’s not enough for me. We must go further.

HOW DO YOU BEGIN TO EXPLAIN YOUR WORK, THE SHOP TO THE UNINITIATED?

It’s a challenge actually, that I like to meet, when people come not knowing what is the shop about. People must be accompanied a little bit. If we open our bubble a little bit we can receive new information. If we do not open our bubble to other trades too, to other people, then we will continue to roll freewheeling, until the next person who says the market is in crisis is right.

The market is tired of always seeing the same faces. That’s why we have to try to find solutions open to people who never see photography, who’ve never seen a photographer [producing anything] different to what’s in the mainstream news feed, that’s the challenge.

For example, with the African storyteller, you sit down and you shut up. You just fully listen to them. We’ve lost that: the tale, the richness of the tale. Without it, the thing is only to sell or not to sell, or try to convince. But we must not try to convince people, it is useless. People are clubbed all week by other people trying to convince them to buy this or do that, and we are far from this type of trade. We aren’t here to convince. We are here to pass on tales, at least in my opinion.

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

©

©

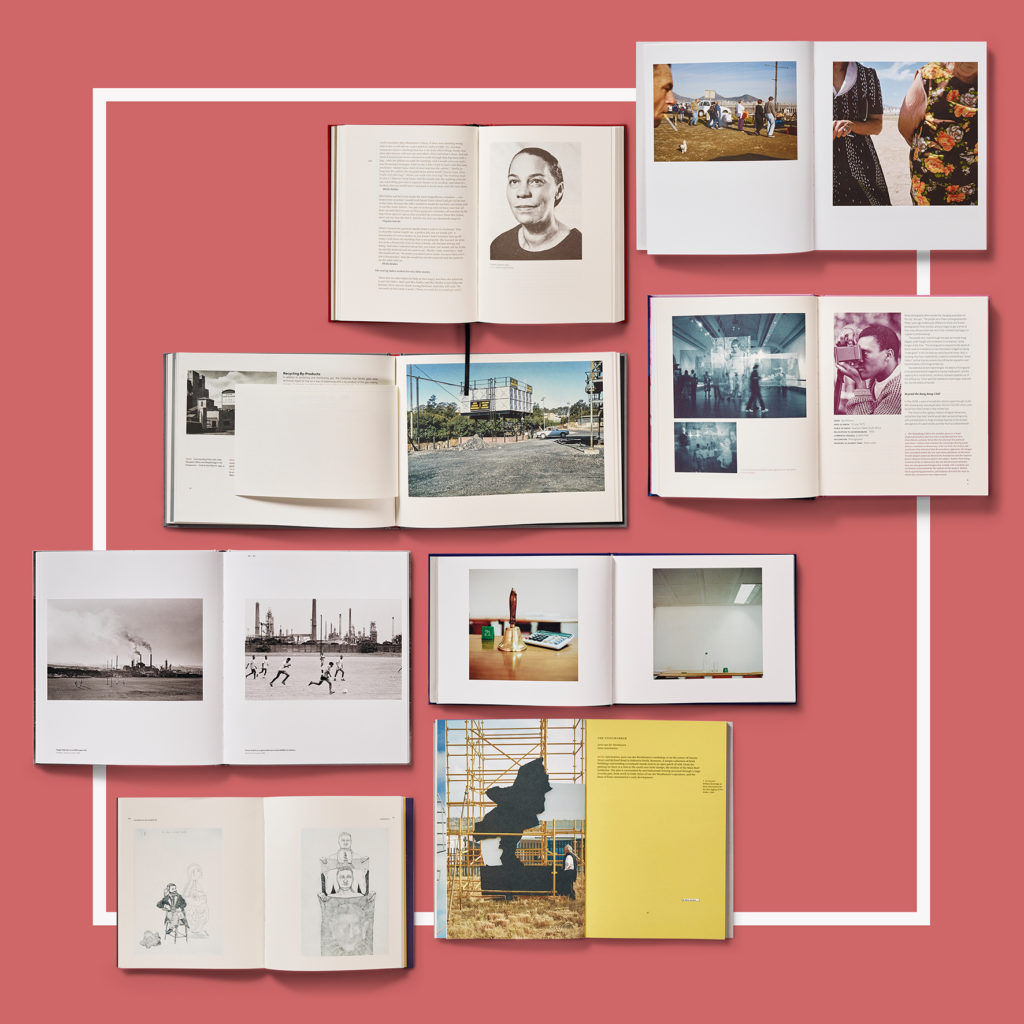

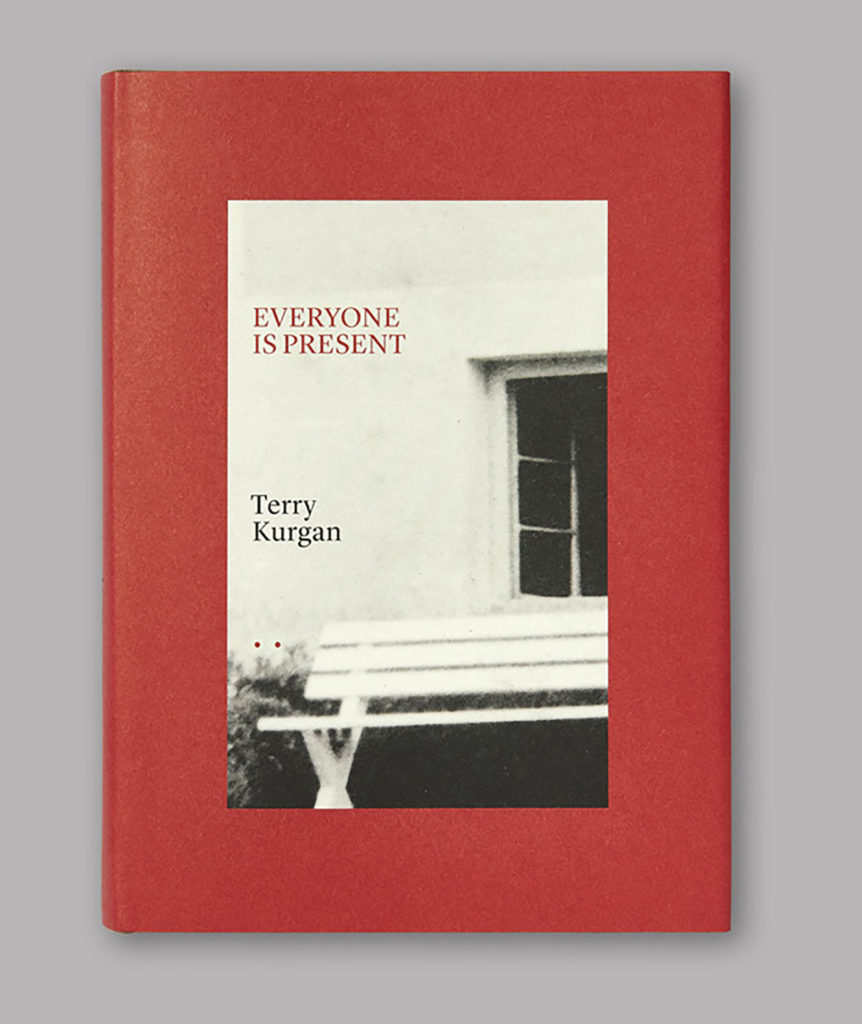

Bronwyn Law-Viljoen and Terry Kurgan run the south african publishing house Fourthwall Books together. The first idea of the company created in 2010 was to publish visual books that they themselves would like to own. Today, they published 38 books and received international awards, in a country where independent publishing is rare, and independent art publishing even rarer.

HERE IS HOW IT STARTED

Fourthwall Books was established in 2010 in Johannesburg by Oliver Barstow and Bronwyn Law-Viljoen. Oliver left for Amsterdam in 2015, at which time Terry Kurgan became co-director and partner.

When we started out in 2010, we saw a unique opportunity to publish high quality books about South African and African art, culture and architecture for a growing audience of readers, artists, cultural commentators, art historians and curators in South Africa and abroad.

THE FIRST BOOK

The first book we published was Writing the City into Being, and the author, Lindsay Bremner, had received a grant to publish it. She is an architect and not a photographer, but her photo essay of images of Johannesburg was included in the book and set the tone for the kind of publishing we like to do: interesting stories told through images and text.

We included the photographs of Alastair McLachlan, Ben Law-Viljoen and John Hodgkiss in our second book, Fire Walker.

Our first real photobook was David Southwood’s Milnerton Market.

OUR POINT OF DIFFERENCE

Our books represent cutting-edge book design and typography and combine images with thought-provoking text. We did not want to reproduce other models of art-book publishing (large, flashy, coffee-table type books; exhibition catalogues; retrospective/overview books) but rather find a new formula for local art publishing that would take very seriously the relationship between image and text, and would draw on the best of South African writing (fiction and non-fiction). We wanted to make serious and well-produced book objects that combined intelligent writing with interesting visual material.

At the same time we wanted to make books that matter in our local context, that had something to say about our city and our country. In the five years of our existence, we have made books about Johannesburg, Marikana, public space, migration, xenophobia, the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange, public transport in the city, a renegade South African composer, Afrikaans youth culture, mine effluent, the South African pavilion at the Venice Biennale, a flea market in Cape Town, child abuse, the first black South African opera company, rural KwaZulu-Natal, and waste recyclers in Johannesburg. We have translated some of our books into isiZulu, isiXhosa, Setswana, Portuguese, French and Afrikaans. Each project speaks to an important aspect of South African art, culture and society, providing insight into difficult social issues and provoking new ways to help address or think about them. They do this through text and image.

THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE

Finding Funds. Staying solvent. The biggest challenge has always been, and still is, being able to fund the production of the next book. South Africa is a small market, and we only print between 500 and 1000 of each book. Our volume of book sales does not even begin to enable more production/publishing. We always have to fund-raise in order to publish the next book. Shipping costs to the rest of the world are very high from South Africa, and this limits our ability to distribute our books overseas.

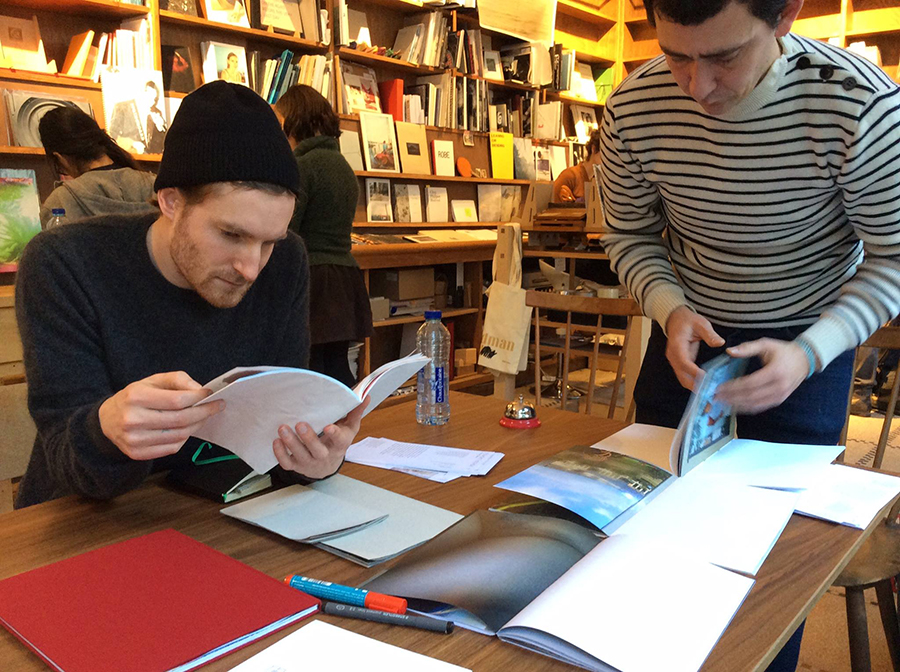

Michael Mack & Bronwyn Law-Viljoen in Conversation

HOW TO SELECT PHOTOGRAPHERS

Photographers bring us projects on a fairly regular basis, and we select based upon the conceptual strength of their book idea/ subject matter and the formal strength of their work. We have to find their topic/theme/project of interest, and we have to also take into consideration whether they/we will be able to find funding for the book, and also, whether it is a book we think we can market and sell.

ON WHAT STAGE IS THE PROJECT WHEN YOU TAKE IT ON

At many different stages. Sometimes there is a body of photographs, and we decide it needs a writer, or a few writers. Sometimes we receive images and text at the same time.

CHANGING OR NOT CHANGING THE DUMMY

This is the design process. We keep working on a dummy until we are happy that book form and book content are communicating perfectly well together. The book object has to have a good relationship with the book content, and we keep shaping the dummy until we are at that point.

IMPACT ON THE PROCESS

We work closely with the photographer/artist/writer towards a book that we think works best. So we have an enormous impact. We work on every part of the editing, design and production process.

DESIGNERS AND PRINTERS

We always use the same designer, but use different printers and processes depending upon the budget we have available to us, and the book object/look/feel we are interested in (and who can produce it) etc.

THE PRESS CHECK

Occasionally we are. It is not always possible because of the cost of travel to wherever it is that we are printing. We usually order test proofs.

Terry Kurgan, Fourthwall Books, at the Johannesburg Art Fair

THE DISTRIBUTION

In South Africa we distribute through Jacana Media. In the rest of the world we distribute through Idea Books in the Netherlands.

PROS AND CONS OF ART FAIRS AND FESTIVALS

We have not been able to afford to travel ourselves or our books to international book and art fairs, but locally, they have been excellent for sales, for networking and also for the broader recognition of our books and our brand.

WHAT TO THINK ABOUT SELF PUBLISHING

It can work very well if you know how to take your book to market.

AN ADVICE TO THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO WANTS TO PUBLISH HIS FIRST BOOK

The photographer should be very clear about the conceptual shape of the project. They should be looking at many, many books and thinking about what is possible in the medium and what approach suits their work.

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

© Honey Rose Studio, Mexico City, Mexico, 2018

From the series ‘Autoportrait’

© Martin Parr Collection / Magnum Photos

© Honey Rose Studio, Mexico City, Mexico, 2018

From the series ‘Autoportrait’

© Martin Parr Collection / Magnum Photos

The British photographer and Magnum Photos member Martin Parr has been described as a “chronicler of our age” and a world authority on the photobook.

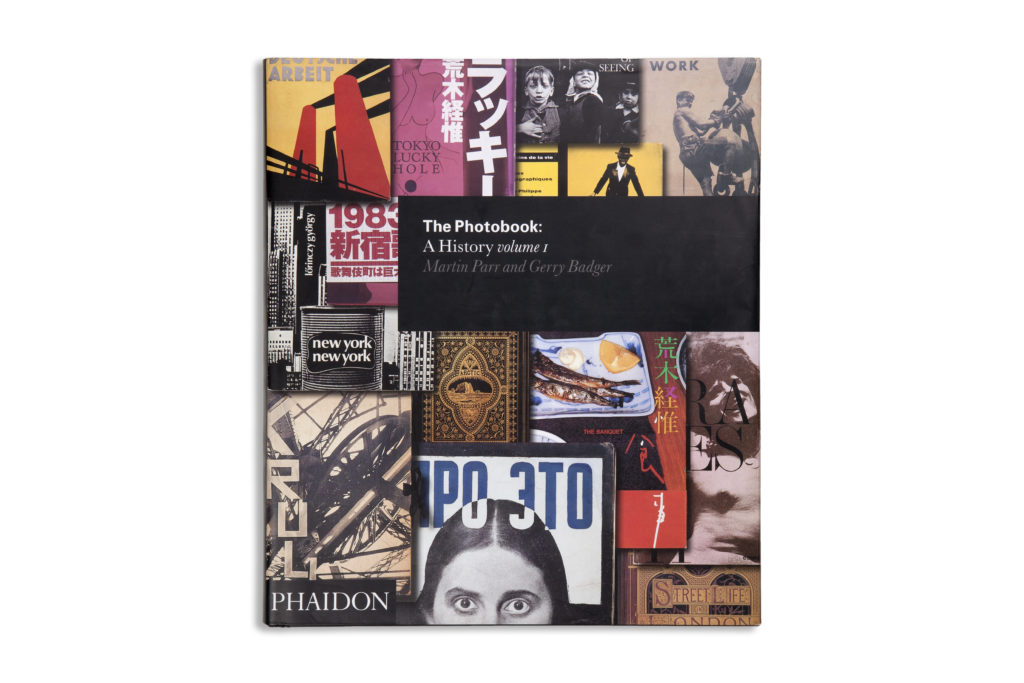

Parr co-authored The Photobook: A History in collaboration with well-known photobook collector Gerry Badger, and contributed to Badger’s collection of 13,000 photobooks. The collection was acquired by Tate with the generous support of Maja Hoffmann’s LUMA Foundation in 2017. Built up over 25 years, the collection includes self-published amateur work, mass-produced books and iconic publications by renowned photographers as Araki and Hans Bellmer. The entire collection will be catalogued and made available to the public through the reading room at Tate Britain.

-

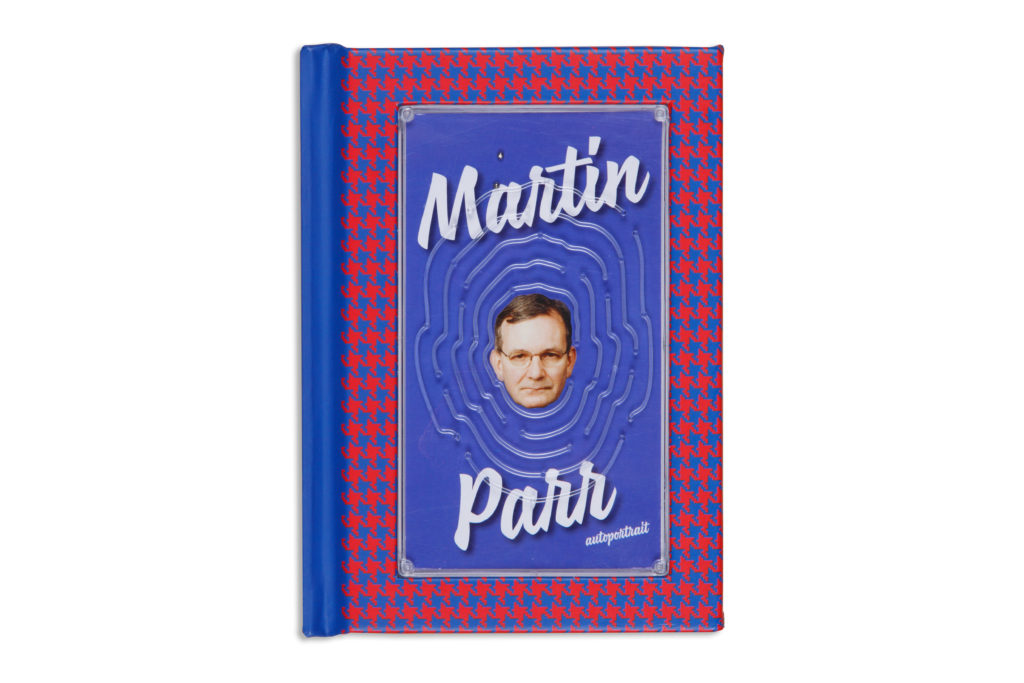

Autoportrait. Published by Xavier Barral. 2015. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Autoportrait. Published by Xavier Barral. 2015. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos -

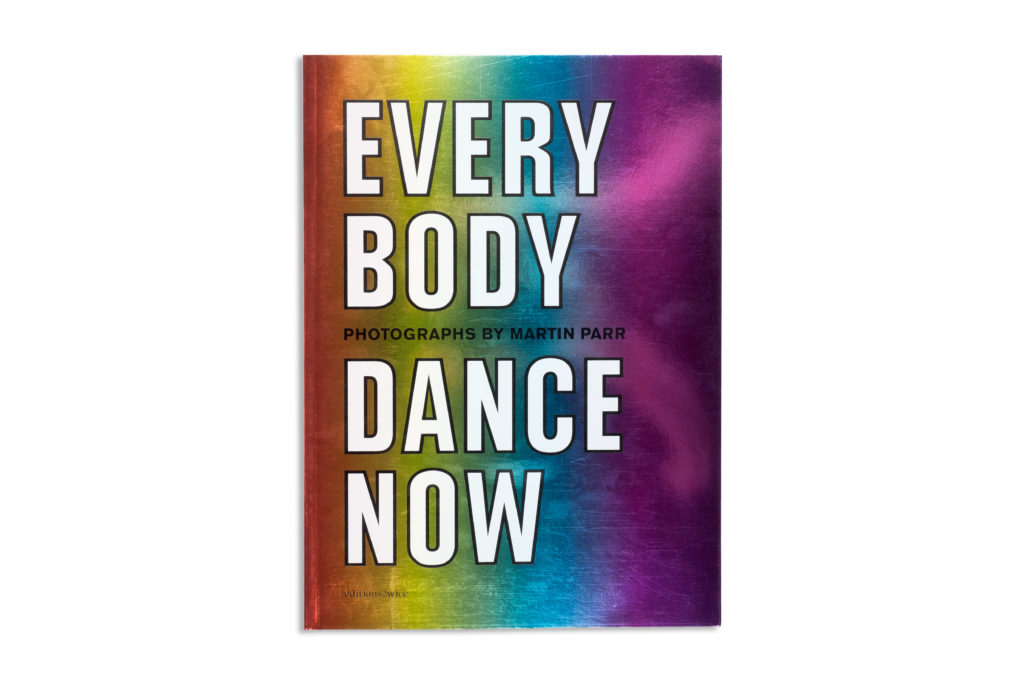

Everybody Dance Now. Published by Editions2wice. 2009. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Everybody Dance Now. Published by Editions2wice. 2009. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos -

The Photobook: A History Vol 1. Edited by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger. Published by Phaidon. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos 2004.

The Photobook: A History Vol 1. Edited by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger. Published by Phaidon. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos 2004. -

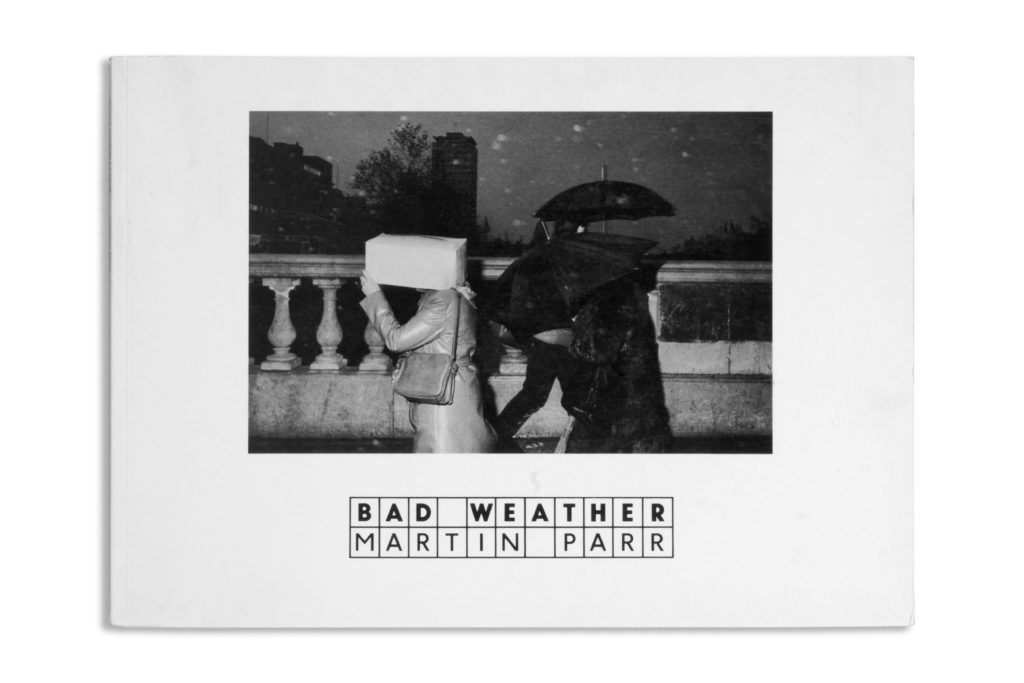

Bad Weather. Publsihed by Zwemmers. 1982. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Bad Weather. Publsihed by Zwemmers. 1982. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos -

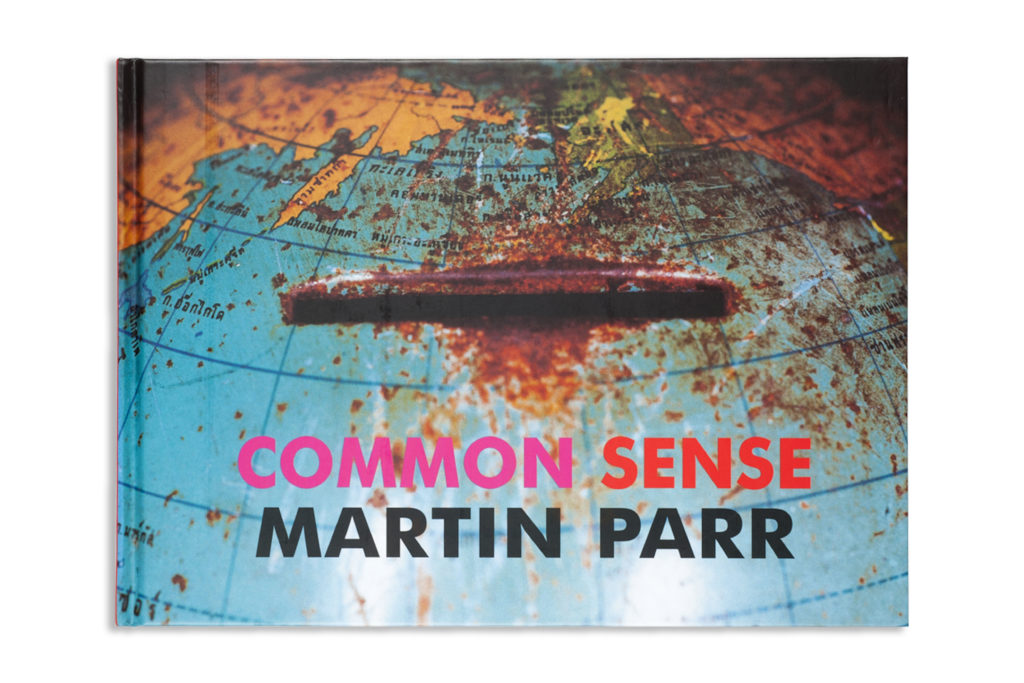

Common Sense. Published by Dewi Lewis. 1999. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Common Sense. Published by Dewi Lewis. 1999. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos -

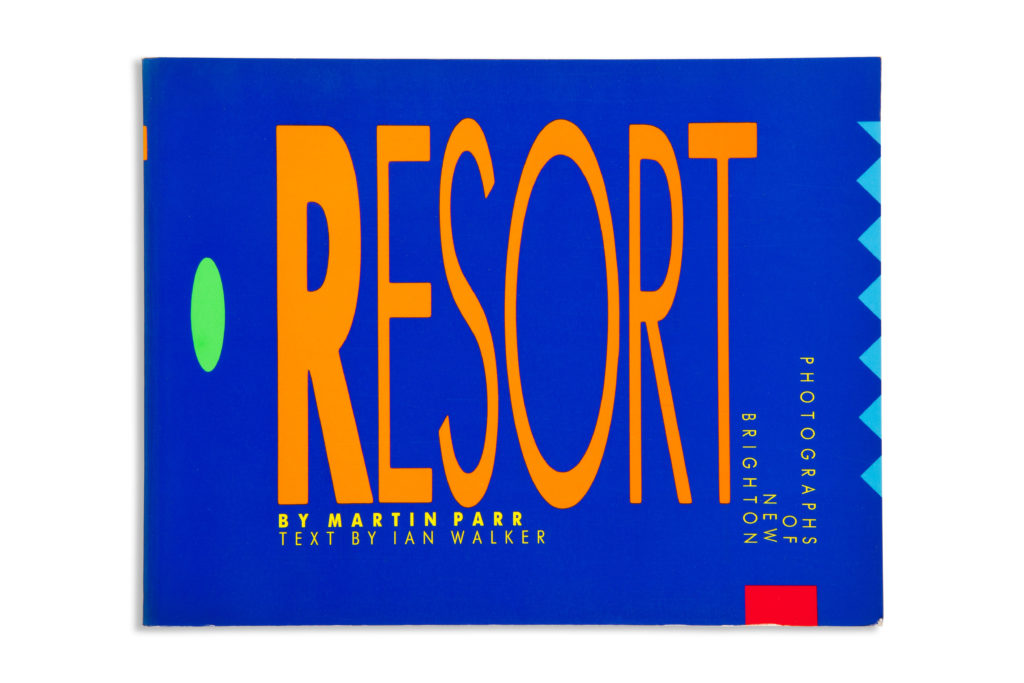

The Last Resort. Published by Promenade Press. 1986. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

The Last Resort. Published by Promenade Press. 1986. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos -

Return to Manchester. Published by Manchester Art Gallery. 2018. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Return to Manchester. Published by Manchester Art Gallery. 2018. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos -

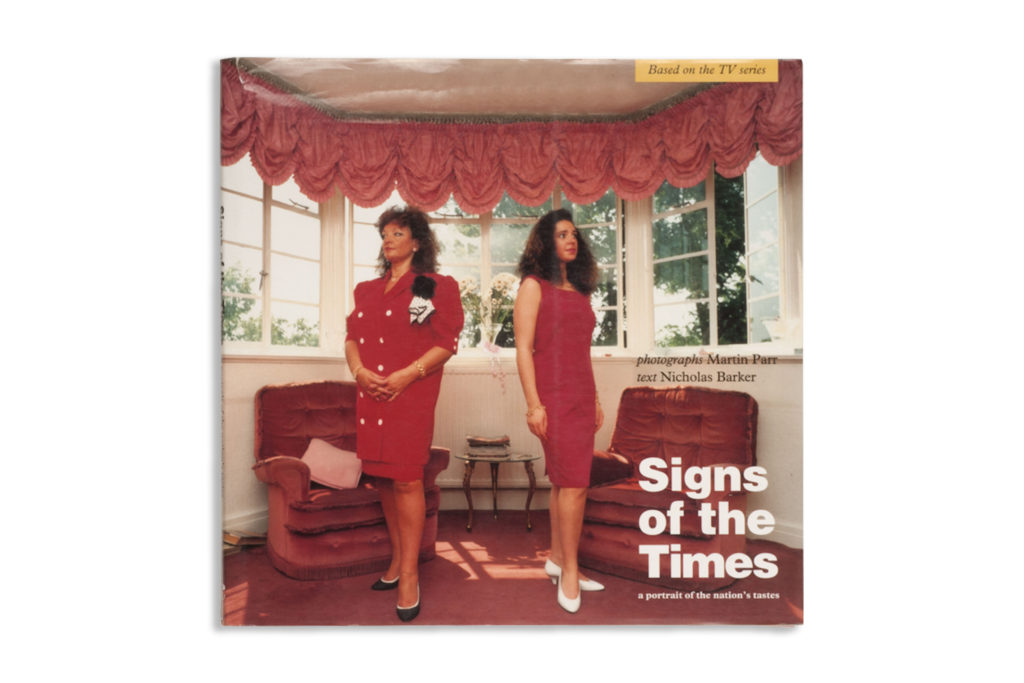

Signs of the Times. Published by Cornerhouse Press. 1989. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Signs of the Times. Published by Cornerhouse Press. 1989. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos -

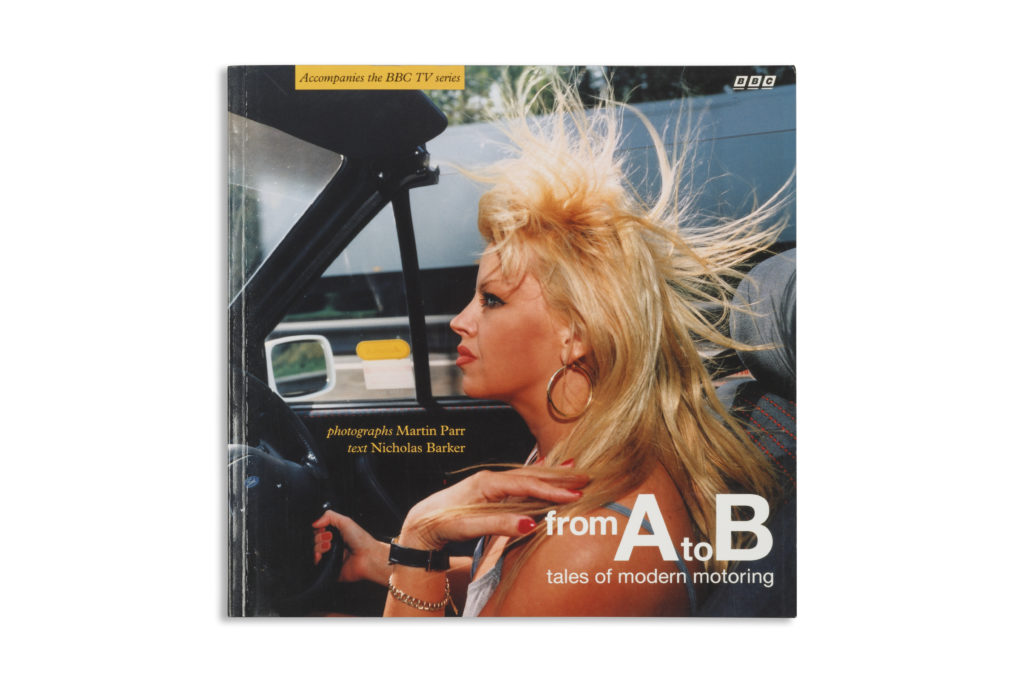

From A to B. Published by BBC Books. 1994. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

From A to B. Published by BBC Books. 1994. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

IT STARTED WITH “BAD WEATHER”

I would not call it a turning point, really it was just exciting. It was much more exciting then, as I have so many books published now. The question is to know what the best platform is, because you can have an exhibition, the internet, but there is still nothing better than a book. I can’t’ remember if we did a dummy, really. We must have had some kind of sequence, some shape of form, but I can’t remember making one. It was a long time ago, nearly 40 years ago. It was then, and still is now, the best way to have the work out to an audience. You know it was published by Zwemmer, but it was originally published by someone else. Then they went bankrupt, then someone else took over, and they got drown to it, so it made it easier for the Art Council. Then it came out and then, after two years it was remaindered so I bought all the copies. It was very cheap. .

DID YOUR PASSION FOR PHOTOBOOKS COME FROM MAKING PHOTOBOOKS?

Obviously I started doing books before starting collecting them, and then that became a real passion, and then I started a collection of around 12-13 thousands books, which are now gone.

WHY DID YOU SELL YOUR COLLECTION TO THE TATE?

It had become a liability, and it was not insured. People were borrowing constantly, and it became an interruption. I wanted to keep it in the UK, and I also wanted to help the Tate to further their reputation in photography.

WHAT’S THE STORY BEHIND YOUR ICONIC BOOK, THE PHOTOBOOK, A HISTORY?

That was an idea that Gerry [Badger] and I had been thinking about for a number of years, and we found the right editor, PHAIDON, and we just thought it was the right moment and we made one volume. Then we realized it was a totally amazing book we had to make two volumes, and then, terribly obvious, we made Volume 3.

WHAT DID YOU LEARN MAKING THESE BOOKS?

It made me concentrate [on the medium], looking for and researching books from China, Latin America, Japan–all the territories we don’t often include in the history of photography. The history of photography developed beyond the usual places, which are Europe and America, like in Latin America. It’s all over the world; my job is to try to embrace those territories somehow marginalised.

HOW DO YOU KNOW WHEN A BODY OF WORK IS READY FOR A BOOK?

You just have a hunch that it’s the right moment. Sometimes books come out of commission, commercial exercises, and then long standing projects that you build up over many years, Above all it’s your enthusiasm that tells you it’s right to publish.

DO YOU EDIT ALONE OR WITH SOMEONE?

I often involve a publisher. And of course I get involved in the sequencing. Sometimes the publisher presents me with a sequence that I really like. Sometimes I do it. Sometimes we do it together.

WHAT ARE THE PROS AND CONS TO SELF-PUBLISHING?

In self-publishing, you take control entirely, you pay for yourself. It’s probably cheaper than going with a publisher: they ask you for money, as they often do. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. You have automatic distribution with an established publisher. But you have to remember that most books come and go and no one notices it. There are thousands of books published every year, and most of them sink without a trace.

WHY ARE PHOTOBOOKS IMPORTANT?

As I mentioned before all photographers agree that it is the best way to get their work out. When you buy their book, it’s like buying a share in a company: you believe in that book, you believe in that photographer, and it’s like showing your commitment by buying it.

THE COMPARISON IS VERY CAPITALISTIC

The world of photobooks is capitalistic, as well as being very aesthetic.

WHAT MAKES FOR A SUCCESSFUL BOOK?

Many great books are not sold out, they’re rather reprinted or whatever. The successful book comes with the work, and the thrust of the book comes together with the right design and the right concept and it just works. You know it when you see it.

WHAT MAKES A BOOK COLLECTIBLE?

One that you like. As simple as that. One that you can have an intimacy with. It’s very personal and subjective.

DO YOU STILL BELIEVE THE PHOTOBOOK IS ”AN UNDERESTIMATED ASSET IN THE CULTURAL HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY”?

Now the estimation has grown hugely the last 20 years. There is still a lot of attention for books and not to many of us, but a lot of people, are constantly in an old debate. Books are becoming a lot more collectable. Times have changed, but one of the things we wanted to achieve has actually happened.

WHY COLLECT PHOTOBOOKS OVER PRINTS?

It’s cheaper than buying prints, more pictures for your money.

WHAT IS NEXT ?

More books! Some good, some bad.

SO YOU’RE STILL COMMITTED TO PAPER?

Yes! People love the physicality of the book.They can smell it, they can handle it, you can give it to someone. You can’t do that with something on the internet.

ANY ADVICE TO THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO WANTS TO PUBLISH HIS FIRST BOOK ?

Make sure the work is good.

interview by Carine Dolek

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

©

©

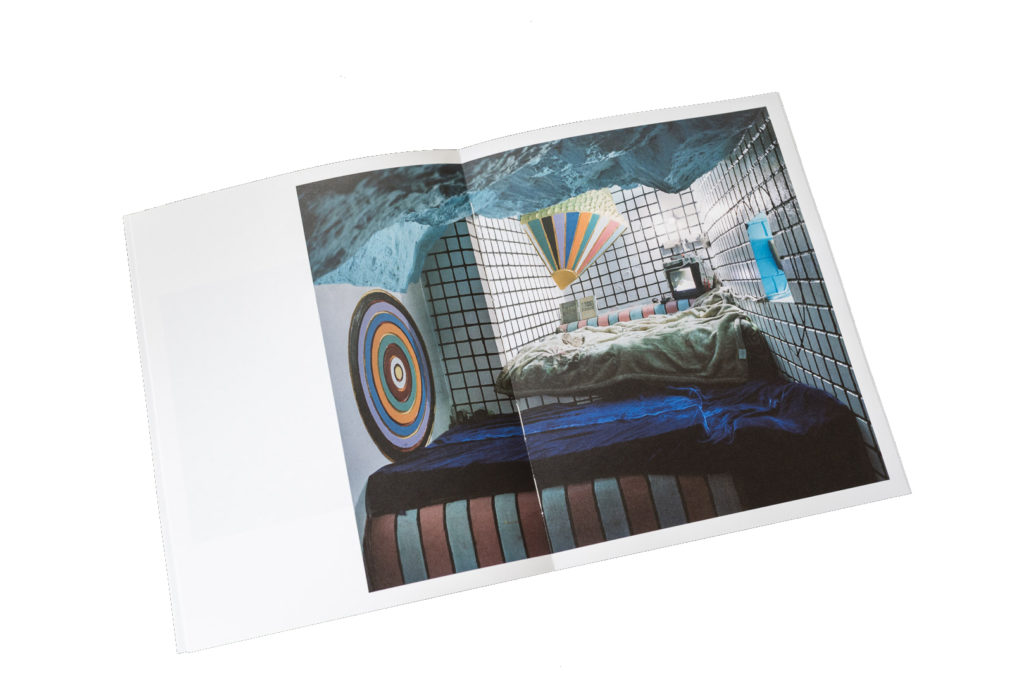

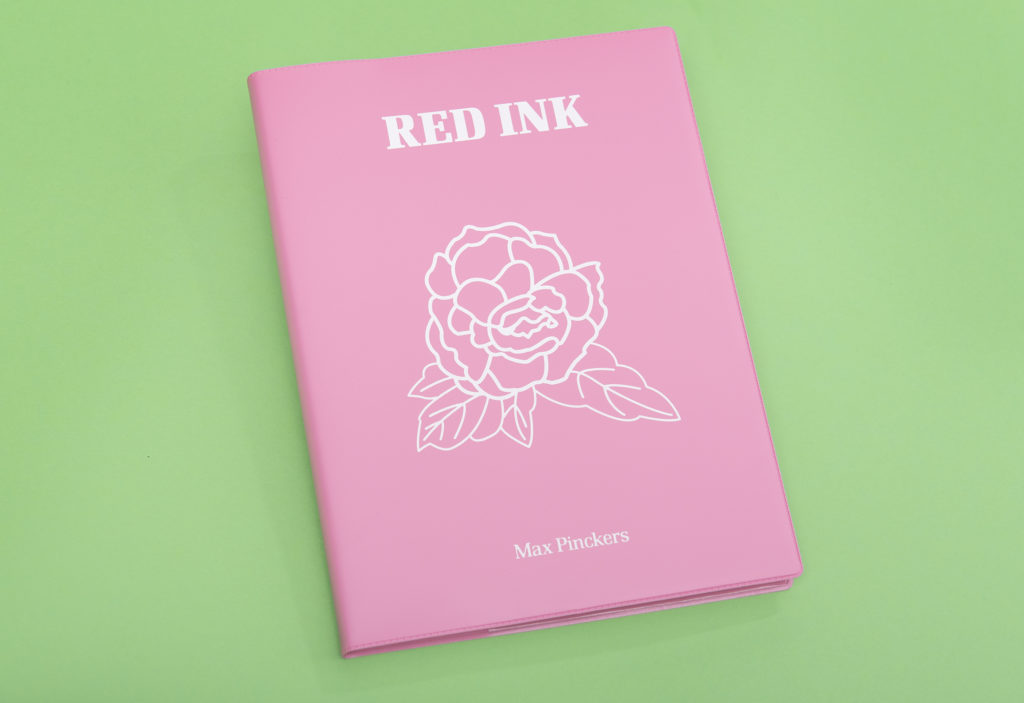

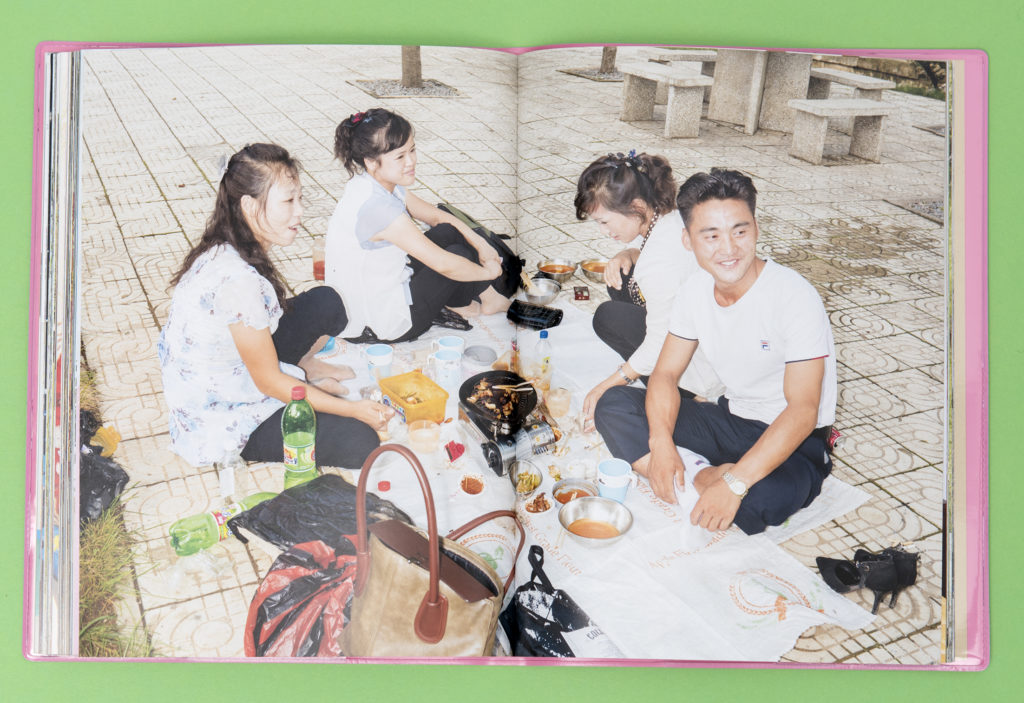

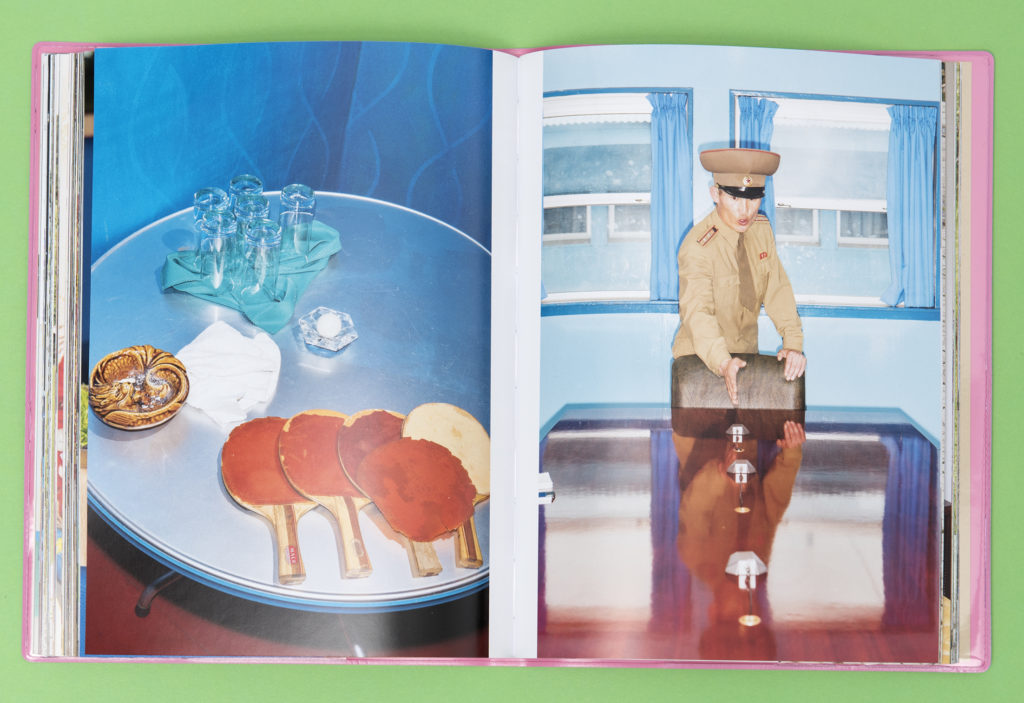

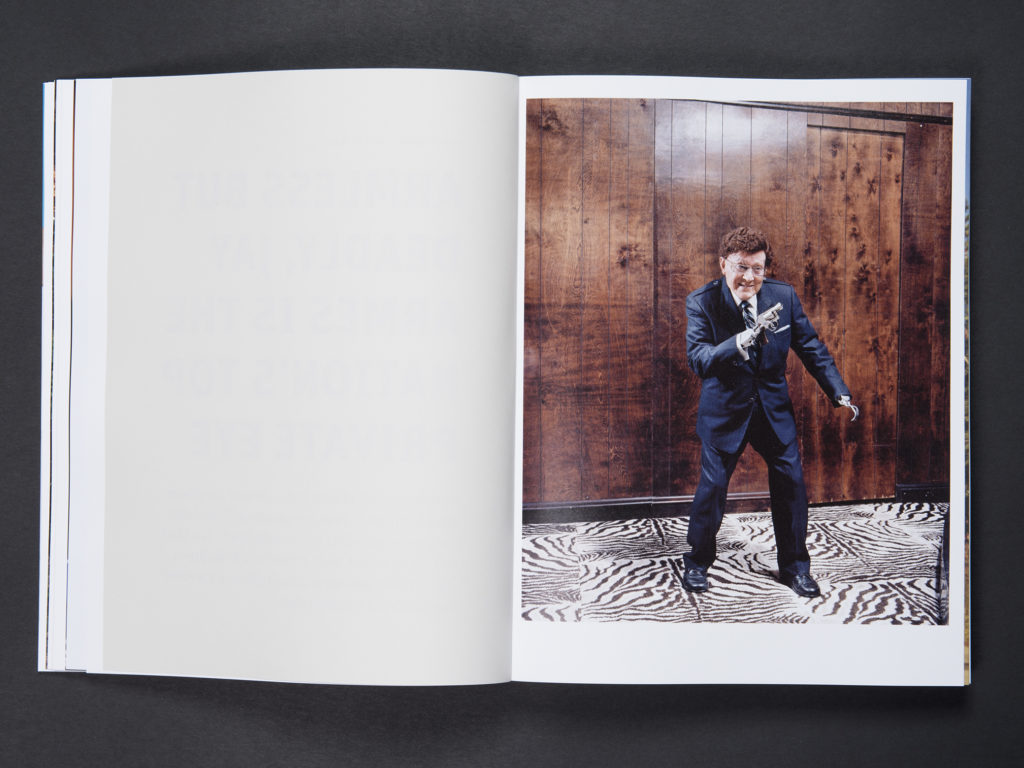

Max Pinckers is a Belgian photographer. He has self-published his books The Fourth Wall (2012) and Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty (2014), Lotus (2016), and Margins of excess and Red Ink, both released in 2018. He founded his publishing house, Lyre Press, in 2015. He won international awards, including the M. Hans Vossen Prize, a Photographic Museum of Humanity grant, the Edward Steichen Award Laureate and the Leica Oskar Barnack Award.

http://www.maxpinckers.be

HOW DID YOU START OUT?

My first book, Lotus, was made in 2011 as a collaboration with another photographer, Quinten De Bruyn. I was still a student at the Academy, in my bachelor year. We made a kind of a Dummy and printed 40 copies.

Quintin and I wanted to explore the aesthetics applied in documentary photography. We wanted to over-aestheticise documentary pictures and explore the subject of transgender women in Thailand, also known as ladyboys.

We combined our photographs with photographs the ladyboys themselves took, which were very amateuristic, and brought the two types of aesthetics together.

WHY A BOOK?

Working on the project, we already knew we wanted to make a book, because it’s a way to create a kind of narrative. I don’t like to use the word narrative so much because it becomes a kind of anti-term, but it’s a way that you can

build up a series of images compiled at the same time. With a book it’s final, everything is there, but you can also bring two disparate registers together. So, for example, we hid the ladyboys’ own pictures behind flaps in the book, so that you first see only the photographers’ point of view and then you get to reveal another aesthetic, another way to approach the book.

Books allows this way of working. I didn’t have any experience of making books, so we really had to learn as we went along. We didn’t completely know what we were doing back then.

HOW DID YOU GO ABOUT GETTING IT PRINTED?

I sent an email to all the people I knew appreciated my work. I said ‘I’m making a dummy book, but I need money to print it because it’s still expensive.’ Then I thought, instead of printing five copies, why don’t I just ask everybody who would like a copy to pay up front? So it was kind of pre-ordering, but in a way that the book couldn’t be distributed. It was quite expensive. A book cost €60 or something because it was digitally printed in a very small run, about 40 copies. Everybody just paid the price of the production, then got a book.

We didn’t made any profits. We produced maybe 10 copies for ourselves and the everybody else got a book.

So that was it, very basic. Our plan was to send the 10 copies that we had to publishers and ask if anybody was interested. I did contact some people, maybe I didn’t put enough effort into it, but at a certain moment, I hadn’t got any response, nobody was really interested, so we kind of put it on the shelf and thought ok, maybe one day we can publish it.

One year later, when I made my second book, The Fourth Wall, I self-published and printed 1,000 copies. Lotus stayed on the shelf until 2016 and then I remade that book in a bigger edition.

HAD YOU CONSIDERED CROWDFUNDING?

When we did Lotus, crowdfunding didn’t yet exist. We did crowdfund for The Fourth Wall, which was was also a practical consideration: the whole book is designed to be printed on newspaper, but the Dummy couldn’t be printed on newspaper because you need a minimum of a 1,000 books to even turn on the offset machine. So the Dummy was on normal paper, which was a bit weird because the design was adapted to newsprint. So because it had to be on newspaper print, I had to make 1,000 books, so I had to crowdfund the money I needed.

I had no distribution plan whatsoever, so when the book was printed, maybe 150 or 200 books were sold on the crowdfunding platform, but I had 800 books in my living room that had to be distributed.

HOW DID YOU COME TO THE ATTENTION OF MARTIN PARR?

First thing I did was send a copy to all my favourite photographers and curators and people who interest me in the art world. Little by little, I started getting emails from online bookstores. People started asking if they could write about the book. Step by step, I learned the process. And then I had a break-through moment.

Martin Parr chose The Fourth Wall as one of his best books of the year and put it on a list. I was not so familiar with these lists, but all of a sudden, the next day, most of the books were distributed. I got so much exposure out of nowhere, and that really lifted interest in the work.

SO THAT KEPT YOU GOING?

I’m now on my fifth book. I work together with my wife. We deal with the distribution and we built up our own system, our own way of sending the books. We work with a lot of very loyal people who support us, who always buy our books. Self-publishing has really become part of my own practice as an artist, it has become part of the work and I really enjoy that. That doesn’t mean that I’ll never publish with a publisher. I would of course be interested in doing it.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN USING A PUBLISHER AND SELF- PUBLISHING?

The main problem in self-publishing is the distribution, because you can’t only go so far. I’m sure there are publishers that you can work with and be free to do what you wanna do, who trust you, where there is a mutual trust.

For the last book [Margins of Excess], our print run was 15,000 books. Red Ink was 8,500. Those are the same kind of run sizes that a big publisher would do, and we can distribute the same amount of books a bigger publisher would. But, of course, a publisher has a distribution network that can ensure your book is in every museum store around the world and that every book store stocks it. In self-publishing, you’re limited to very specialised places. So, if I work with a big publisher, I would be interested in doing a very high print run and getting it out as far as possible, so that it reaches a public that I cannot reach myself.

HAVE YOU BEEN APPROACHED BY PUBLISHERS?

Yes, and the deal they offered me wasn’t financially interesting. It’s a very tricky business. If you publish a book with a big publisher, most of the time, it’s at the same time as a big exhibition in a museum or something like that, or you have partners that pay for the production of the book, or some kind of collaboration between different publishers that carry the cost and so on. When I was approached, there was no partnership with anything else, it was just one to one. Then the construction gets very tricky financially. It’s never been the case where I say, ‘Hum, that’s something I couldn’t do myself.’ I’ve always thought ‘Can I do it myself and stick with my own agenda?’

SO YOU TAKE A PUNK ROCK, DIY APPROACH?

Exactly! And that’s the only way you get to know how it works. A lot of people ask me, ‘Should I self-publish?’ I say go for it, but it’s a lot of work. You have to learn step by step, how it works from talking to people, getting the business side of it, dealing with the percentages and commissions.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED FROM MISTAKES?

One of the really difficult things is the number of copies. So we’ve overshot, we made a book with way too many copies. There are books that we made too few copies of, that sold out so quickly they never were even seen at books fairs. And, when you start making pre-sales of the book, a lot of the books are already gone before the distribution.

Timing is another lesson: when you release a book it has to coincide with festivals or exhibitions. These are things that I learned as I went along.

HOW DID YOU LEARN ABOUT PRICES AND PAPER SIZES?

Pricing and paper are also something you learn as you go along. After making a couple of books, or collaborating with designers, or having a close relationship with the printers that make the book or the binders, you realise that there are ways to economise on production prices.

For example, if you use a certain size of paper, it exactly fits an offset sheet, which is 70x100cm, and you can use that one sheet to maximum efficiency. If you go one centimetre bigger you might only use half of the sheet, and the price of the book doubles. All these little tricks! So when you’re making a book, you’re thinking, ‘Maybe we should use this size or that size, or maybe we shouldn’t. Should we go for a unique size, at greater expensive? Can can economise on some other choice?’ That’s all a part of the process, and it’s part of working with the designer. Until now, we’ve never had to make a compromise. It’s always been exactly what we wanted it to be.

WOULD YOU CREATE THE SAME BOOK TODAY AS YOU DID THEN?

Probably it would be different. But I also like that it’s been done this way, and that it’s kind of part of that time and artistic process. It has its place.

CAN YOU SPEAK ABOUT THE PROS AND CONS OF THE INDEPENDENT SCENE?

Here on the boat (Polycopies, Paris, November 2018 ),

everybody knows each other, everybody’s friends, everybody supports each other. That’s a beautiful part of the—I don’t want to use the term ‘underground publishing scene’ but it does pose an alternative to the mainstream, more popular work that is out there at Paris Photo. The most beautiful things are here.

The downside is that it can be a bubble, a kind of hermetic environment where sometimes I feel it’s a bit too disconnected from the things that happen outside. It also creates a space for a lot of things to be created, and not everything might be good. But that’s not bad: the more things are made the better, so fantastic things comes out. But, on the other hand, when you go to a fair you can’t differentiate anymore between all the things that are being published. One of the roles of a publisher is to curate: what is a good work, what should be published and what shouldn’t. So you could say the critique [of the independent scene] is that everybody gets free rein.

IS THERE A RECIPE FOR A GOOD BOOK?

No, there is no recipe. For me, a good book is a book that translates the concept of the work in the best possible way. It’s not a particular form, it depends on what the artist wants to say, on what the works want to say. If the book complements the concept or the intention, then it’s a good book.

ANY WORDS OF ADVICE TO THE ARTIST MAKING THEIR FIRST BOOK?

I’m very happy myself with how the process went so I don’t have so much. Maybe be extremely critical about the choices you make, take your time, think about what you

do, reflect on the world and always make sure that your own intentions and your own work is given the utmost respect. Make sure it’s done in a way that you want to work. Create some kind of independence for yourself and stick with that, and be very critical about the conditions in which you work, about how you work. Of course talk with as many people as possible, make as many relationships as possible and try to get your work out there, that’s the most important thing.

interview by Carine Dolek

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

© Marek Szczepanski

© Marek Szczepanski

Ania Nalecka is is a graphic designer, art director and book designer. She has designed, among others, “Swell” by Mateusz Sarelo, “Distant Place” by Sputnik Photos, “Karczeby”, by Adam Panczuk, “Boiko”, by Jan Brykczynski and “The first march of gentlemen”, by Rafal Milach. The books she designed have been awarded at the POYi – The Best Photography Book Award, Bratislava Photomonth, ParisPhoto/Aperture Foundation Photobook Award, The New York Photofestival, Photography Book Now, Art Books Wanted International Award, and Publication of the Year, Fotofestiwal in Lodz. She has also co-curated Sputnik Photos’ exhibitions Stand By and Distant Place, Photo-eye for Best Books of 2012 (best books by Sputnik Photos) and the Curated Bookshelf with Foam Museum in Amsterdam. http://nalecka.com

-

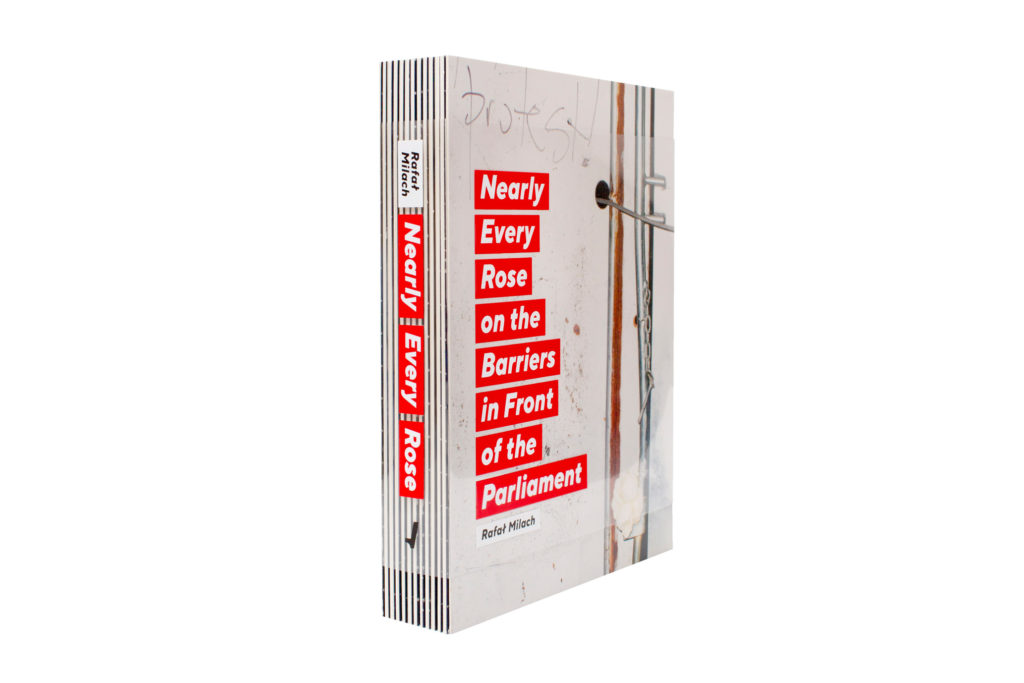

book cover by Rafal Milach.Nearly Every rose...

book cover by Rafal Milach.Nearly Every rose... -

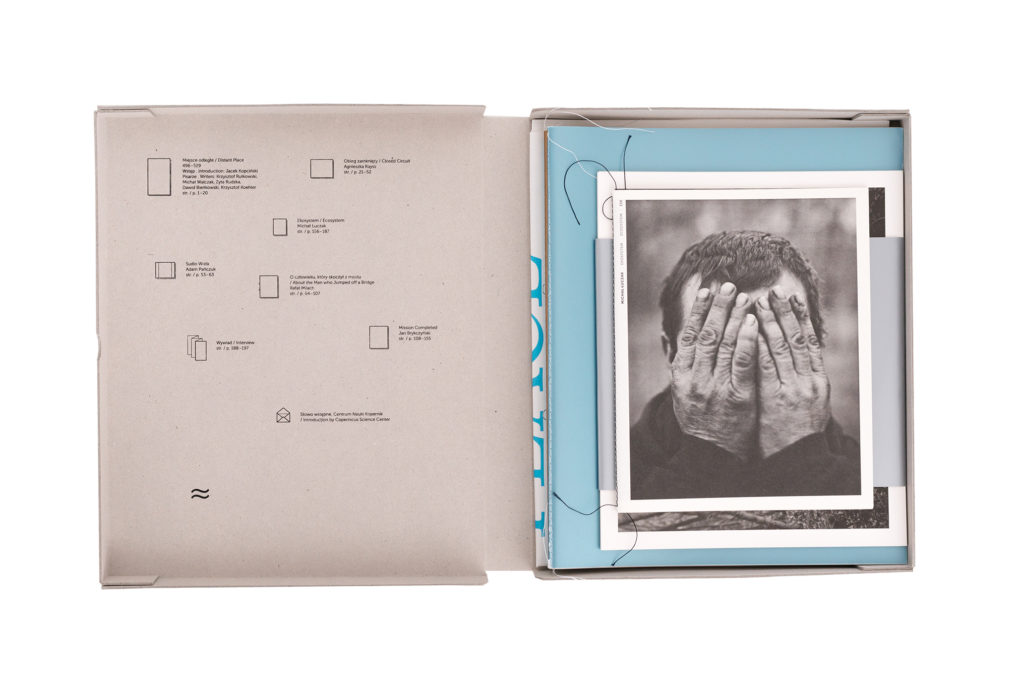

book Distant Place

book Distant Place -

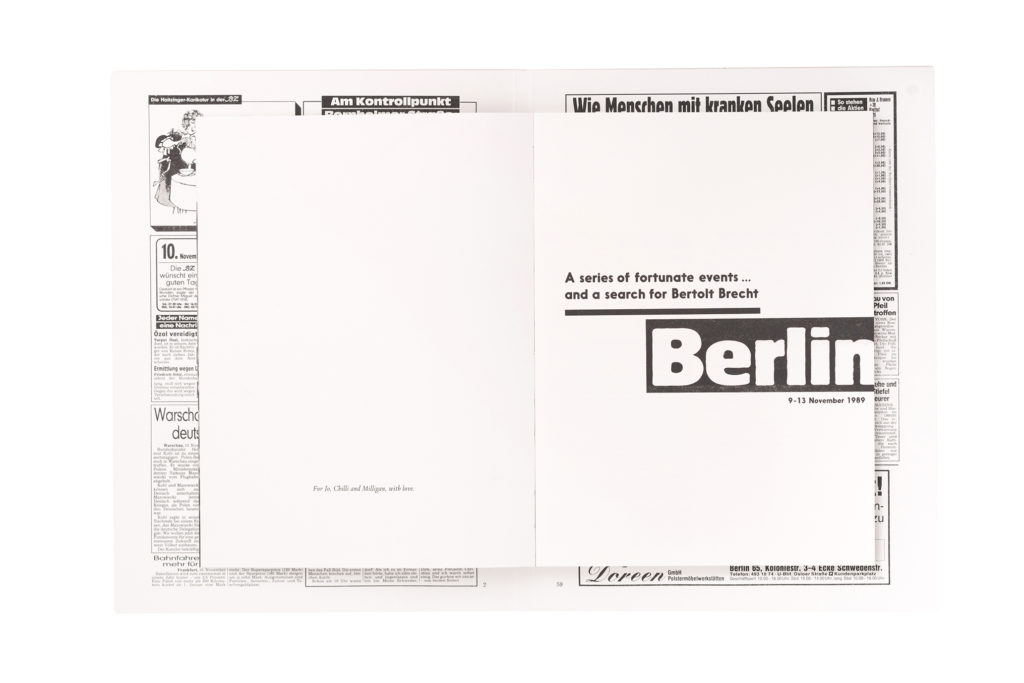

book by Mark Power.Die Mauer ist weg!

book by Mark Power.Die Mauer ist weg!

HERE IS HOW IT STARTED

I start publishing for good in 2008, although I designed my first book in 2002 : “The love book. The best of my dreams” by Slawomir Rumiak, 2002. It was graduation year in academy of fine arts, at printmaking and graphic design faculty. I was doing my master about concept of open form in art (interactive art), still something drew me towards books.

MY POINT OF DIFFERENCE

I think i am very classical designer. I believe that being honest counts. Also, that context and form reduction works.

THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE

Not having absolute control over production process – I am control-freak, and dealing with contradictory expectations of artist, sometimes their self-handicapping strategy. We all have issues

HOW TO SELECT A PROJECT?

I think it goes both ways – we select each other. However, I am looking for mature collaboration, for the partner.

ON WHAT STAGE IS THE PROJECT WHEN YOU TAKE IT ON?

All above. However sometimes working on an almost ready dummy can be more time and effort consuming than starting from edit and sequencing. What I have learnt so far is, that there is no such thing as ”easy project”.

CHANGING OR NOT CHANGING THE DUMMY?

I talk, find out about the story, analyse the formal solutions, if they follow the story. If yes and there is no need to change, I don’t.

IMPACT ON THE PROCESS

Sometimes we talk from the beginning what the story is about, what should be in the texts. There are times I do edit and sequencing, but I prefer to work with the third person – additional point of view always helps. It doesn’t mean that chronologically always sequencing determines design. Can be opposite – we ask for the edit and sequencing that follows the book structure, because the structure already tells the story.

THE PRINTER IS A LONG TERM RELATIONSHIP

I try to build longer relations – I have two printing houses in Warsaw I work with since 2007. I helps to work out standards and work-flow – to some extent.

PRESS CHECK, WITH OR WITHOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER?

I am always at the press for final printing, as if it’s possible an artists is there too – sometimes the cost of travel is too big (from USA or Australia). I also strongly recommend investing in wet test print (print test on final press machine on final paper). It save lots of stress, but can save money as well. I am also present during the book binding process.

PHOTOGRAPHER’S IMPACT ON THE FINAL SHAPE OF THE BOOK

She or he is the author, so it should be dominant in terms of what the story is about. I am there to help to translate it into the form of the book. If someone has such a clear vision, that it dictates the design of the book and it makes sense – there is no need for me to interfere, only cross check and guide. Photographers with experience in making books usually have a strong overall vision – like my husband Rafal Milach for example.

INGREDIENTS OF A SUCCESSFUL BOOK

In my opinion, successful book consists mostly a good story – visually (it’s visual language after all) and the way it’s told (edit and sequencing). Then, if all elements of the book (both conceptual and formal) follow and underline it, with no irrelevant ones, it is a success. Book design is really like a jenga tower.

PROS AND CONS OF ART FAIRS AND FESTIVALS

For me:

Pros: illusion that you can have some overview

Cons: it is illusion

For the publisher:

Pros: exposure, sale

Cons: there are too many books

For the book:

Pros: exposure, sale

Cons: there are too many books

WHAT TO THINK ABOUT SELF PUBLISHING?

Same old thing as with anything else : independence vs responsibility. It is not for everyone.

AN ADVICE TO THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO WANTS TO PUBLISH HIS / HER FIRST BOOK

Be honest. First, with yourself – if you really want to make a book out of this particular story. Second, with the viewers – don’t waste their time, don’t underestimate their skills in understanding.

DON’T DO IT VS BEST VISIT CARD EVER

Do it, but not as visit card. It’s not about you. Do it as a record of the story that matters – this is the original purpose of the book I think.

HOW MUCH TO ALLOCATE TO PUBLISH A FIRST BOOK?

Money is very subjective. Maybe as much she/he can afford, having in mind that probably sale won’t balance the costs. And as much it’s needed to make the book she/he likes at the end. Saving 100 euros and then looking at 500 copies of ”compromised” version may not be worth the spare.

interview by Carine Dolek

International Book Design Conference, 2015, Vilnius, Lithuania. Photo by Mantas Puida

International Book Design Conference, 2015, Vilnius, Lithuania. Photo by Mantas Puida

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

© Caroline Warhurst

© Caroline Warhurst

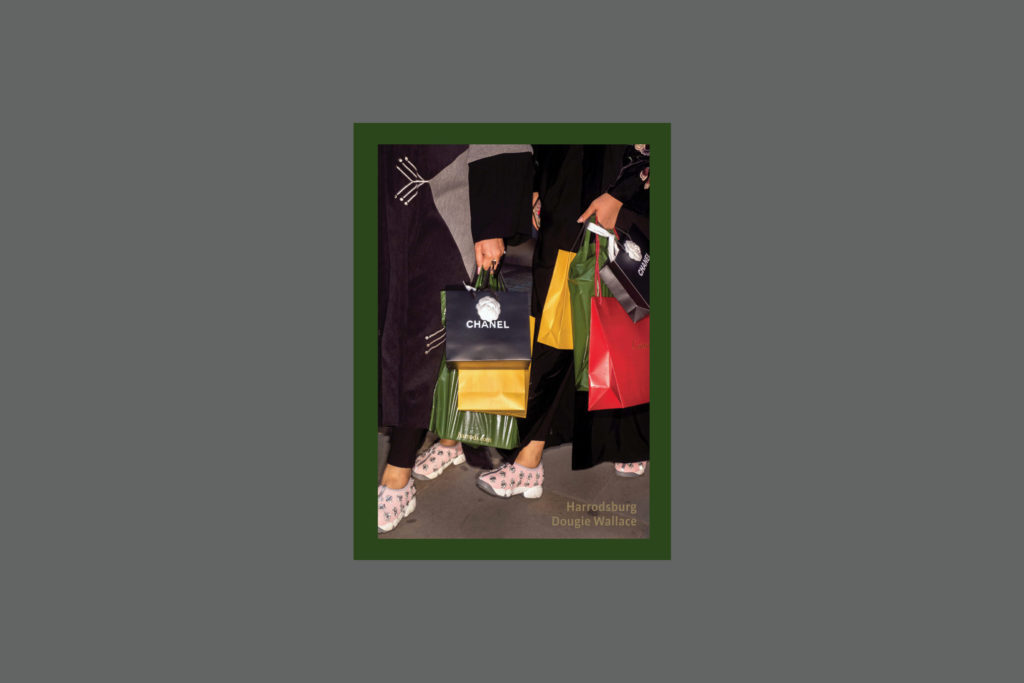

Dewi Lewis Publishing is one of the leading photographic publishers in the world. The company is run by Dewi Lewis and Caroline Warhurst and publishes around 20 new titles each year of leading British and international photographers such as William Klein, Martin Parr, Simon Norfolk, Fay Godwin, Tom Wood, Sergio Larrain, Frank Horvat, John Blakemore, Paolo Pelegrin, Laia Abril, Dougie Wallace and Bruce Gilden. Dewi Lewis aims to bring to the attention of a wider public, accessible but challenging contemporary photography by both established and lesser known practitioners. dewilewis.com

Here is how it started

In 1985 I had set up Cornerhouse, a major Film and Visual Arts Centre in Manchester (since renamed Home). I was director there and we ran an extensive exhibition programme covering all the contemporary visual arts. As part of that we regularly published catalogues. For a variety of reasons I decided that we should start a publishing programme, I felt that this should focus on photography as it seemed to me to be most underrepresented artform in publishing at the time.

Then the first book

In 1987, I published my first book: ‘A Green And Pleasant Land’ by John Davies, but the first book I published through my own company was ‘Children of Bombay’ by Dario Mitidieri, in 1994.

In the last few months before I left Cornerhouse I had helped set up The European Publishers Award for Photography with four other European publishers. Cornerhouse decided against continuing their involvement and agreed that I could participate instead. Dario Mitidieri was the first winner and so his book was my first. Because there were five publishers involved and the print run quite large, the costs were less than they would have been had I been the sole publisher.

I went independent in 1994. As I was setting up the company I also earned an income through arts consultancy work and it was through that, and a small overdraft, that I was able to put together enough money to publish the first book. If it had failed I wouldn’t have been able to continue and I would also have been paying off debts for some time.

On Press with Mimi-Mollica

The biggest challenge

Producing a book is almost always a fascinating and thoroughly enjoyable experience – trying to then sell it is very different, and very difficult. Ultimately the biggest challenge is to be willing to take risk after risk. Nothing is ever certain to be successful and so you have to have continual optimism BUT it must be balanced by a clear sense of realism.

How to select a project

Each year I see many hundreds, if not thousands, of projects. Some through open submission, some through portfolio reviews or from being on juries, others in exhibitions or published in magazines or online. I have no fixed idea of what I am looking for but when I see it I usually know pretty quickly. For me it is about a project that feels new and fresh, a project that holds together, has something to say, and deserves the enormous effort and expenditure that is needed to make a good book.

Dummy or not dummy, that is the question

I don’t really like to work on a finished project that allows minimal input for me. The interesting elements of being a publisher are about the process of putting the book together. Consequently, I am usually involved in every aspect of development from reviewing the initial ideas, working on the edit, then the design and through to the final marketing of the book.

Ideally, I want to be in a position to have a significant impact in helping to form the final work, but it depends on the project. My starting point is always to tell a photographer that they must submit their work in a completed, sequenced form. It doesn’t need to be a finished dummy, but it does need to be a set of images organized in the way that the photographer believes will best tell their “story”. If they do that, then it helps me to understand what they are trying to say. If they were to give me a hundred or so images to select from and edit then the “story” would be mine, not theirs. My role should be different, it should be to help them say what they want to, not what I want to. But I should be challenging their ideas. Ultimately, I’m aiming to help them understand how to most effectively use their visual material.

I almost always tend to change the original dummy. Dummies are handmade objects and often they just don’t work once you move into the industrial process of print production. Sometimes this is because of the economic reality, sometimes because things can’t be physically done in the same way by machine. But, of course, there are other reasons such as the failure of a sequence, too much repetition, unnecessary or inappropriate text etc. etc.

Instead of a dummy, I prefer simply to just see a set of images – laser print outs or whatever – put together in a sequence. If I don’t like the design of a dummy then it can sometimes be hard to see beyond that.

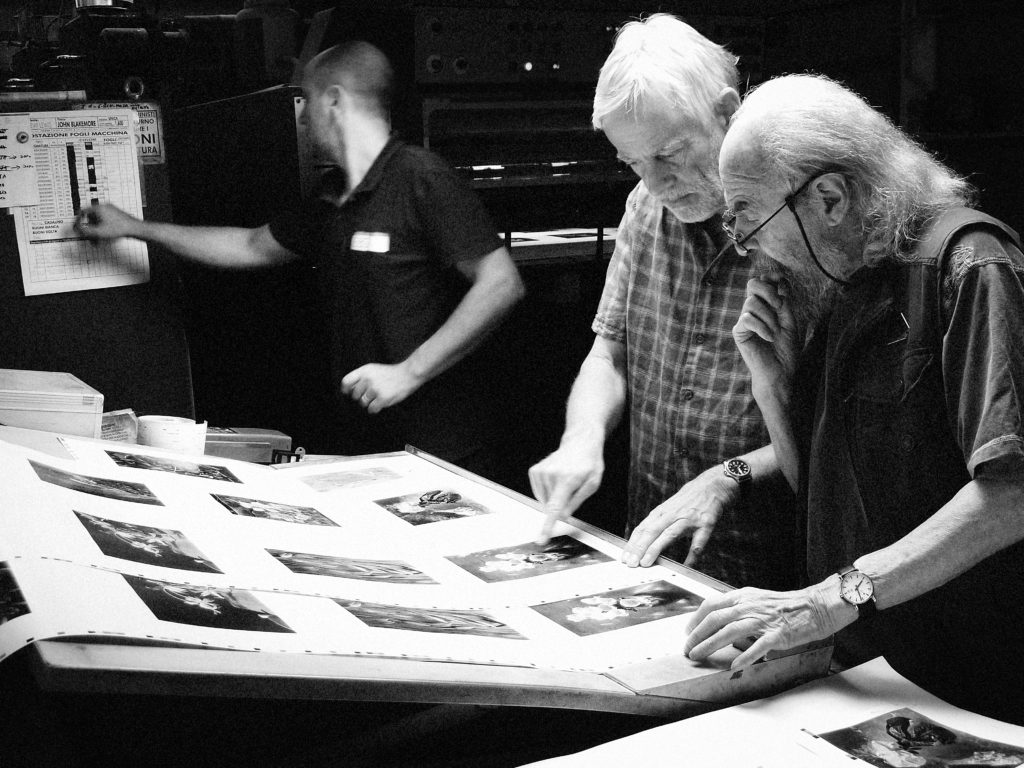

On Press with John Blakemore

Design

I design the majority of our books – at least 80% of them. But I am also happy to work with other designers. We tend to work with an external designer for a specific project or for a specific reason. We have worked with a few designers a number of times but often that’s because the original project has come to us via them.

Press check, with or without the photographer

I still go on press for almost every project (99% of them). I also try to encourage the photographer to attend. The printing process inevitably involves compromises and my view is that I prefer to make those decisions rather than leave it to the guys on press, however good they are. I think that my presence adds a few percentage points to the final quality of a book. As for the photographer I think that it’s important to go on press so that they understand the process and are fully engaged. I want them to be fully involved and to have a real sense of ownership of the final book.

interview by Carine Dolek

During Photo Book Programme an editor, publisher, designer, and printer will mentor you through the process of publishing a photo book. Apply Here

After a difficult judging process, BLOW is pleased to announce the winner of the 2019 FUSE Photo Book Programme is Rosin White for her project “Lay Her Down Upon Her Back.’’

Roisin’s three-month residency will include:

- Collaborative dummy book-making workshops with Read That Image

- A one-on-one workshop with Valentina Abenavoli from Akina

- Editing with the BLOW Photo Editor

- Personal instruction from renowned publisher Dewi Lewis

- One-on-one workshop with the director of Plus Print

- A professionally-designed dummy by Unthink

- A printed dummy by Plus Print

- Presentation of the dummy to major publishers during The Rencontres d’Arles

- Accommodation

- Access to the facilities at D-Light Studios

- 3 complimentary issues of BLOW Photo Magazine

The task of selecting a winner was incredibly difficult and we could not have imagined the level of the entries received. All six of our shortlisted projects presented strong material worthy of a book.

Laura Steven – Him

Jan Jurczak – Life Goes On

Miriam O’Connor – Tomorrow Is Sunday

Judith Helmer – Identically Different

Joan Alvado – Cuban Muslims, Tropical Faith

All shortlisted photographers are receiving:

- 3 complimentary issues of BLOW Photo Magazine

- invitation for the next edition of FUSE

Congratulations to Jan Jurczak and Laura Stevens, whose applications inspired further discussions with our FUSE partners to see how we might expand the programme. Jan and Laura will both receive a special award, individual 2.5 days workshops, which will include:

- Personal consultation with Read That Image

- Editing with theBLOW Photo Editor

- Insights into the publishing world fromDewi Lewis

- One-on-one workshop with the director ofPlus Print

- One-on-one design workshop with Unthink

- Accommodation (2 nights)

- 3 complimentary issues of BLOW Photo Magazine

- invitation for the next edition of FUSE

Thank you to all of this year’s applicants. We were delighted with the quality of the work submitted and cannot wait to get FUSE 2019 started!

Keep eye on our website and social media to follow Roisin through her process.

©

©

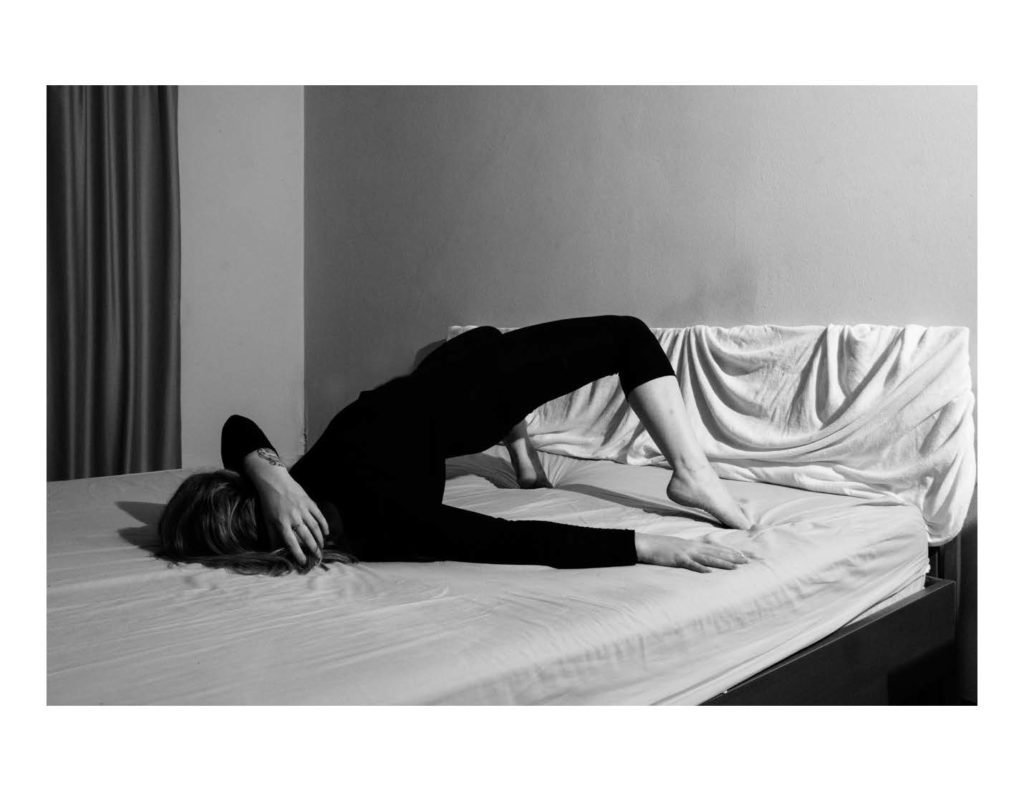

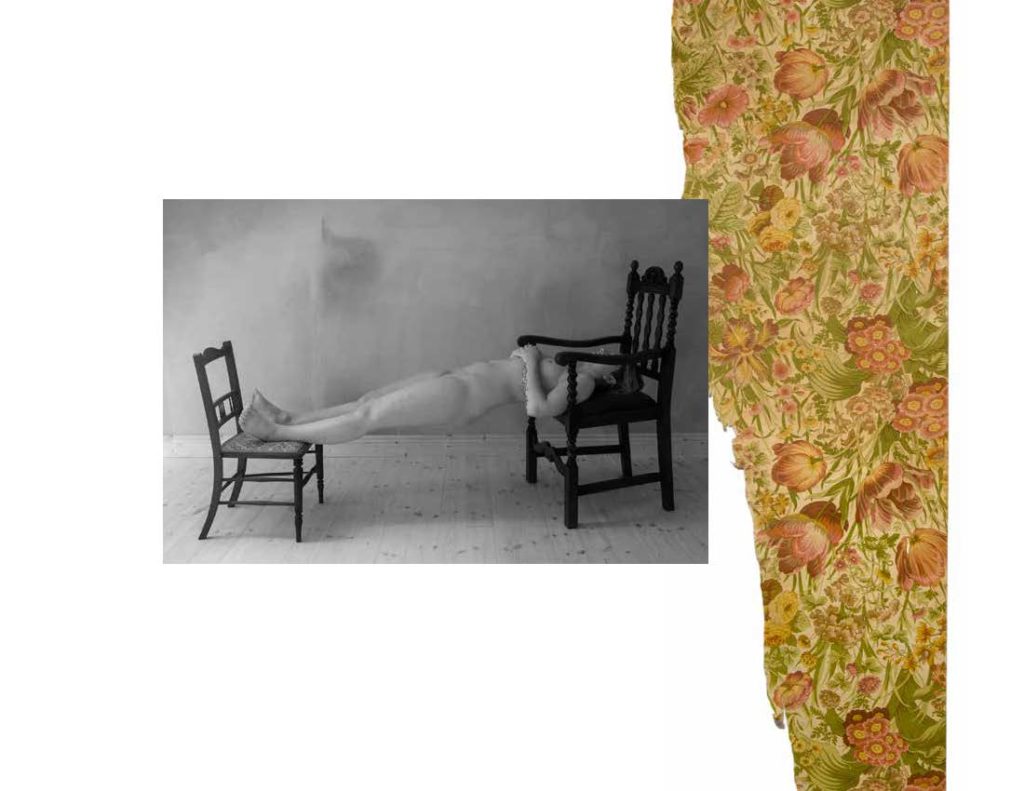

Róisín White is a visual artist based in Dublin, working primarily with photography, while incorporating drawing, sculpture, and collage into her practice. Róisín holds a BA(hons) in Photography from DIT, and certificates in Ceramics and Sculpture from NCAD.

Róisín White’s work draws from archival materials. She has an interest in exploring lore and the fictional narrative that can be discovered in discarded imagery, previous understandings agitated, and new meanings drawn out. Roisin’s sculptural work brings her photographic work into the three-dimensional and builds on means of photographic reception.

White has exhibited her work in Ireland and across Europe, with her debut solo exhibition at The Library Project in August 2018. She was selected to represent PhotoIreland at Futures Photography platform, and was selected from an international open call to take part in Parallel European Photography Platform in 2018/9. Her project “Lay Her Down Upon Her Back” was selected for the third edition of New Irish Works in 2019. White was selected to take part in residency programmes, How To Flatten A Mountain residency at Cow House Studios in 2017, In-Between Shores residency with Ardesia Projects and JEST Gallery in Italy in June 2018, and Cow House Studios in February 2019.

Recent exhibitions include “I See Crimson I See Red” at Elizabth Fort in Cork City, supported by Tactic Studios and Cork City Council, in January 2019. White will have a solo exhibition as part of her residency at The Darkroom in Stoneybatter in April 2019. Róisín has recently been granted the Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council Emerging Artist Grant to put towards a new body of work.

LAY HER DOWN UPON HER BACK

This body of work that examines the legacy of the 1880s treatment known as The Rest Cure. It was generally prescribed to women who were deemed to be of nervous disposition, aneamic, or hysterical, and involved them spending up to two months on bed rest, over-feeding, isolation and electrocution. This treatment has since been discredited, but its legacy in women’s healthcare remains today. The Rest Cure cultivated mistrust in women’s pain and discomfort, and made the female patient solely dependent on her male doctor. The method in which the Rest Cure was administered solidified power relations between doctor and patient and ensured that she would be submissive to her treatment.

“And here lies the trouble: there are women who mimic fatigue, who indulge themselves in rest on the least pretence, who have no symptoms so truly honest that we need care regard them. These are they who spoil their own nervous systems as they spoil their children, when they have them, by yielding to the least desire and teaching them to dwell on little pains.”

(Weir Mitchell, S. 1877).

©

©

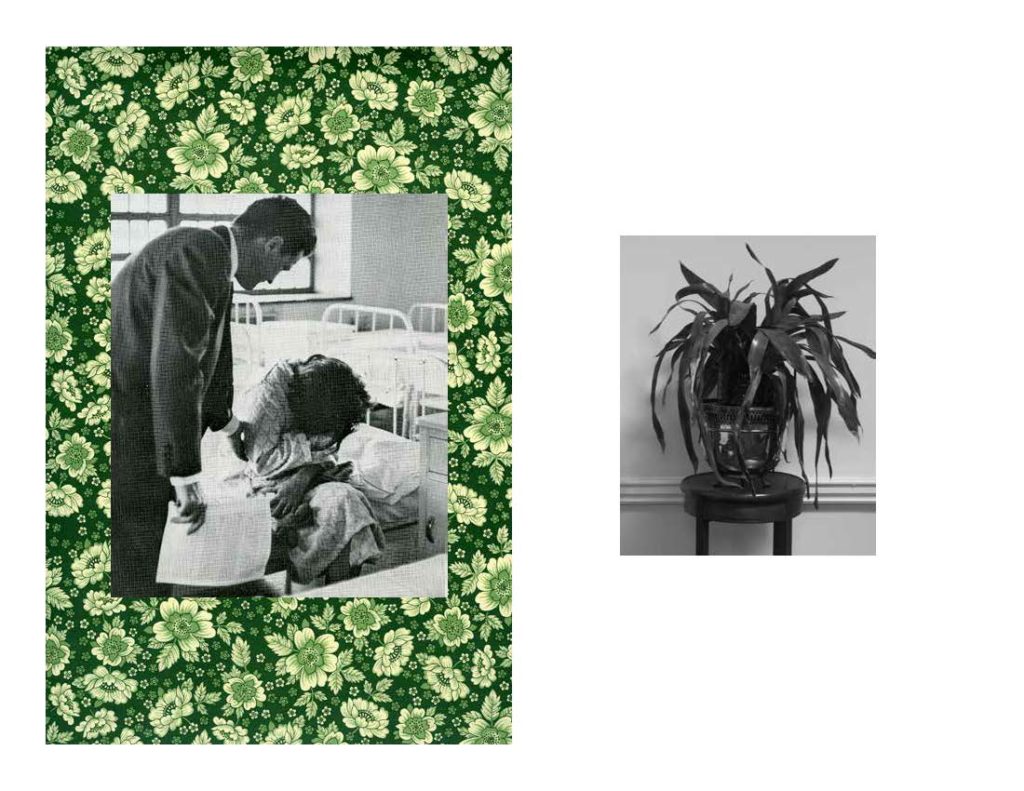

Laura Stevens (b. 1977 England, UK) holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Arts and Design from Leeds Metropolitan University, and a Master of Arts degree in Photography from the University of Brighton.

Through portraiture and landscape photography, her artistic practice focuses on themes of relationships: between man and woman, longing and loneliness, vulnerability and connection, home and belonging.

Stevens’ work has been the subject of features in GUP, The British Journal of Photography, Marie Claire and Exit magazine, among others publications. She is a finalist in the HSBC Prix pour la Photographie 2019, was awarded as one of the Critical Mass Top 50 by Photolucida in 2018 and 2014, received a special distinction in the LensCulture Emerging Talents Award in 2014, was a finalist in The Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize in 2013 and 2014 and was nominated as a Flash Forward Emerging Photographer by the Magenta Foundation in 2012.

Her work has been shown in museums, galleries and festivals internationally, including Clampart Gallery, The Schneider Gallery, The National Portrait Gallery, The Centre for Fine Art Photography, Galerie Esther Woerdehoff, Fotofever and The Singapore International Photography Festival, with work represented in private collections.

Stevens has produced commissioned work for clients including Le Monde, The New York Times, Wired, GQ, Forbes, The Washington Post, Le Figaro Magazine, F, The Guardian Magazine, The Times Magazine and The Wall Street Journal.

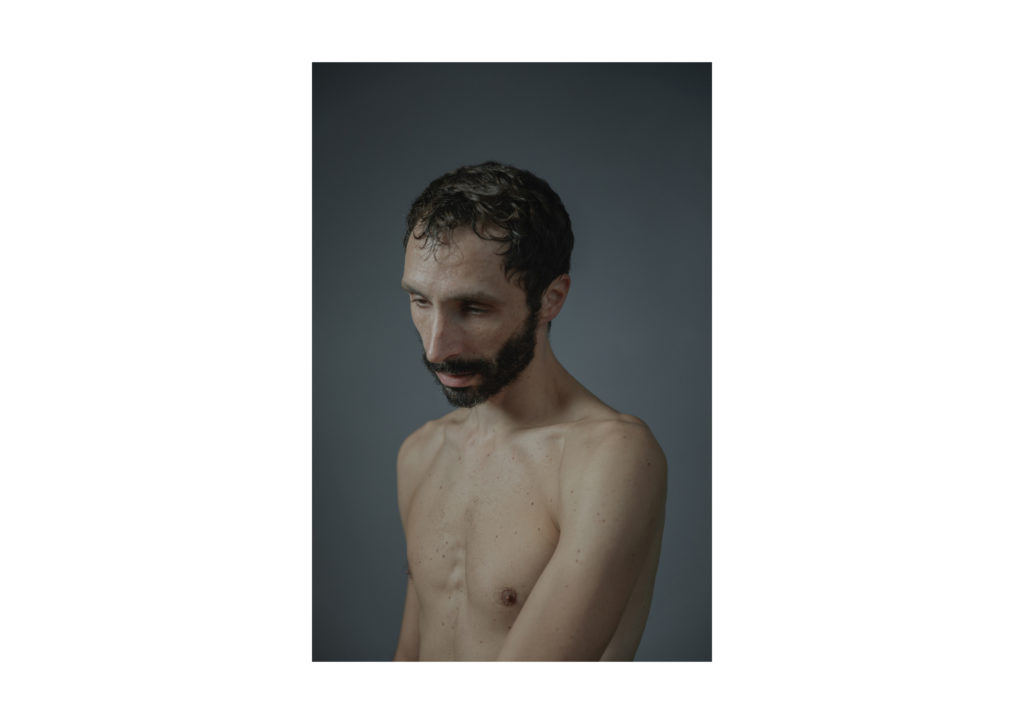

HIM

Over the course of one year I invited over fifty men to my home to be photographed naked.

Most were strangers, and it would be the first time we met. Stripping my bed to a white sheet, my most intimate space became a site for the man to be at his most intimate. An area with defined boundaries to move within, into which I would look, and he would be looked at.

Being a woman, at the age of forty, contemplating the naked male body feels curiously problematic. With representations of the male nude predominantly made by male artists, there is a lack of imagery exploring a female sensual response to male beauty. Regardless of the advances made in recognising women’s capacity for and right to visual pleasure, the historically dominant male gaze prevails.

Pursuing a way of looking at and portraying man, I questioned the cliched symbols of a ‘hard’ and ‘active’ masculinity which deny vulnerability or the supposed feminine qualities of ‘soft’ and ‘passive’. Allowing oneself to be the object of another’s gaze requires yielding one’s control and allowing for a revealing to occur, both physically and emotionally. To be naked-as-an-object – to become a nude – furthers this uncovering. In photographing this series of men I was entrusted with this exposure.

Within this encounter, between him and me, what would I see?

©

©

Jan Jurczak co-ordinates long-term documentary projects in Poland and other countries (e.g. Ukraine, Armenia, Spain). In 2017 & 2018 he was working with Ukrainian population living next to the front line of the eastern part of their country. While performing his projects, Jan tries to get involved into the entire situational context. Jan was born in 1996 in Krakow, Poland. He completed courses at Faculty of Rehabilitation, University of Physical Education in Krakow, and Sociology Department, Pedagogical University of Krakow (2015-18), based in between Warszawa and Kraków. Jan Jurczak popularizes his charity work giving interviews at various media. Recently he started to work on a new project focused on human and nature interactions. Jan is interested in identification of local minorities with surrounding nature, the human body and its delicacy, and environmental problems. Jan loves to climb, practically from his early childhood. He climbs regularly with his closest friends, in nearby rocks and abroad.

LIFE GOES ON

There are 6 million people living in the ATO zone: «the territory of the anti-terrorist operation», as defined by the Ukrainian legislation. It covers parts of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, which for the last 4 years or so has been experiencing armed conflict.

Two worlds function side by side, and the ability to adapt to such a situation is what connects both soldiers and ordinary citizens. Although a conflict around there is so much stability there. Children dance, women take pride in their own appearance, life goes on.

©

©

Irish artist, Miriam O’Connor lives and works in Cork, Ireland. Drawing inspiration from the language, sights and sounds of the everyday, her photographic practice frequently engages with matters which reflect her everyday surroundings and contemplates the manner in which this persuasive medium permeates the way we engage with the world around us. Rather than providing answers, O’ Connor positions photography as a tool for posing questions, a medium in itself that commands interrogation. Her projects have explored themes around looking and seeing; the relationship between camera and subject, and the complex nature of photographic representation.

Her work has been featured in magazines including; Camera Austria, Source Photographic Review, The New York Times and The Guardian. Recent exhibits include, Interiors and Other Landscapes, Sternview Gallery, Cork (2018), RHA Annual Open, Dublin (2018), Encountering The Land at VISUAL, Carlow (2018). Internationally, in recent years, she has produced work for FRESH EYES – International Artists Rethink Aarhus, which was exhibited during Aarhus Capital of Culture, (2017) and shown work in Post- Picturesque: Photographing Ireland at Rochester Arts Center and the Perlman Teaching Museum, USA, (2017). Upcoming shows include, newly commissioned work for Active Archive – Slow Institution – The Long Goodbye at Project Arts Centre, Dublin (Feb 2019) and in The Parted Veil at The Glucksman Gallery, Cork (April 2019).

Her work has been selected for FUTURES, a photography platform that pools the resources and talent programmes of leading photography institutions across Europe in order to increase visibility of its selected artists. In addition to her art practice, O’ Connor also lectures part-time at Griffith College Dublin.

TOMORROW IS SUNDAY

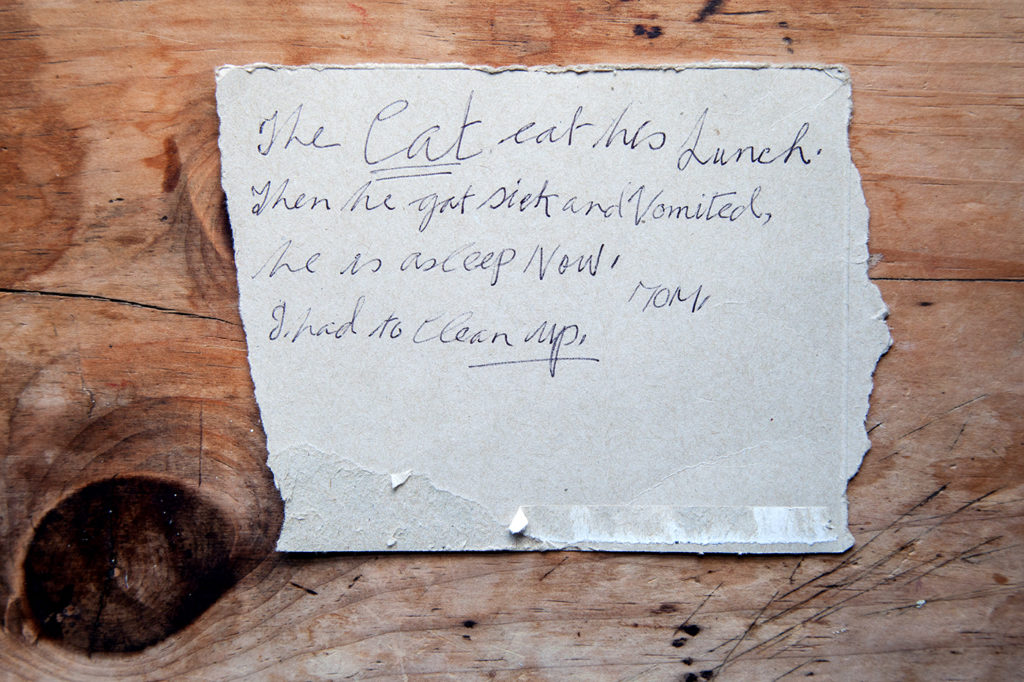

This project engages with my return to the family farm following the death of my brother in 2013. Up until this point my brother had thoughtfully managed the farm for almost three decades, and the task of keeping things going was then conferred to my mother, my sister and I. The project utilises photographs, texts, logbooks, inventories and glossaries, which in differing ways, reflect on how grief is processed through labour and everyday farming practices. This scrupulous approach of logging, compiling and indexing reflects efforts to regain some semblance of order where past and present might begin to reconcile in some way.

©

©

Born in Altea in 1979, Joan Alvado has lived in Barcelona since 2005.

His work is focused on long-term documentary projects that play with the concept of the unexpected, seeking to break with visual clichés and established stereotypes.

His images have been published in media such as Newsweek, The New York Times, CNN, The Washington Post, Bloomberg Business Week, El País, La Repubblica, Der Spiegel, Polka, Hurriyet, VICE, Descobrir Catalunya, among others. Part of his work has been exhibited at photographic events and festivals in Spain, USA, Cuba, Turkey, France, Romania, Slovenia or Italy.

In 2016, his latest project, “Cuban Muslims, Tropical Faith” wins the “New FNAC photography talent” award in Spain. “Cuban Muslims” has also been awarded at the CENTER Choice Awards (USA), and has been selected finalist of the Emerging DST Prize awarded by the festival Encontros da Imagem (Portugal) and finalist too in the Kolga Tbilisi Photo Awards (Georgia). “Cuban Muslims” also receives honorable men-tions in the Visura Grants for Documentary Outstanding projects 2016 and 2017, Gomma Grant 2017 and in the International Photo Awards of 2016. The series has been exhibited in several Spanish cities, and in the festivals Photon (València), Photo Romania, Astoria Photo Walk (New York), and also in the ISO Lab art space of Venice and in the Marion Center for Photographic Arts in San Diego (USA). “Cuban Muslims, Tropical Faith” has been published in Newsweek, CNN, La Repubblica and the PAPEL magazine of El Mundo.

The archive of the project is part of public and private collections in institutions from USA, Germany and Spain.

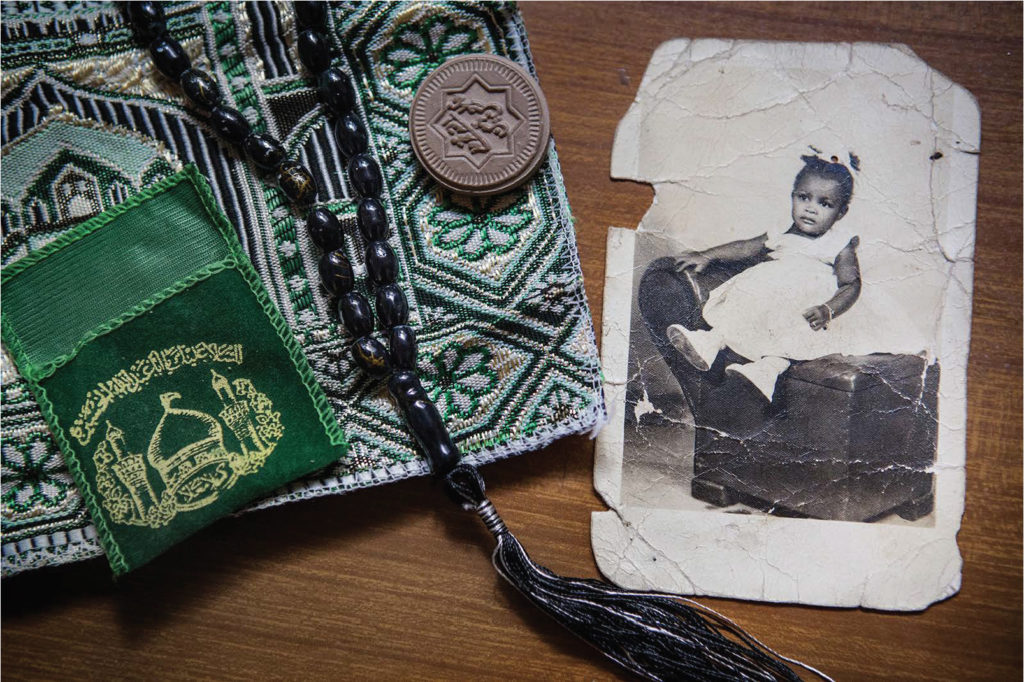

CUBAN MUSLIMS, TROPICAL FAITH

Cuba is one of the last countries in the world where Islam has entered. Although is still widely unknown, the number of Cubans embracing Islam has constantly increased in the recent years. This growth is strongly linked with the current scenario of changes in Cuba, which includes a higher tolerance towards religions. With a current population around 3.000, Cuban Muslims are present in several districts of La Habana but also have expanded to many other provinces, like Camagüey, Santiago or Varadero.

Why a Muslim community is born in the middle of a Socialist Caribbean Island?

The “Cuban Muslims” project is not aiming to give closed answers, but to provide clues for reflection. . By delving into one of the most unique Muslim communities worldwide, an innovative approach about both Islam and Cuba is generated, without dramatic connotations. The goal is to break visual stereotypes, questioning issues like identity, faith and traditions.

©

©

A Dutch documentary photographer working on long term projects exploring personal stories of others often related to identity, family relations and social issues. Her photography is often described as being both powerful and sensitive at the same time.

She graduated from the Fotovakschool in 2017, and won the Keep an Eye Fotovakschool Award the same year. Her ongoing graduation project ‘Identically Different’ won an honorable mention at The International Photo Awards 2017 and has since been exhibited at several venues & photo festivals worldwide, including Festival Circulation(s) in Paris, Photo Beijing in Beijing, Le Voyage à Nantes in Nantes and TEAT Champ Fleuri in La Réunion. She has recently been nominated for the Rabobank Dutch Photographic Portrait Talent Prize (2018), was selected as Dutch New Talent (2019) by GUP and won the prize for best portfolio at the portfolio reviews of BredaPhoto (2018).

She loves the analogue process and prefers to shoot with her analog 6*6 camera.

IDENTICALLY DIFFERENT

The phenomenon of identical people who originate and have grown from a single cell is fascinating. This story is about an identical twin, born on 20 July 1996. They are ‘mono-mono’ twins, not only sharing the womb but also one amniotic sac and a single placenta. Two people cannot be more identical than that. While others always treated them as ‘one’; they knew from a young age all too well how different they were.

After a process of years one of them made the profound decision to follow his long-felt, true identity… Laura became Laurens. This choice led to both Laurens and Yentl having to discover who they really are, as an individual and as twins. I followed them through the process of self-discovery and claim for identity.

Partners

We are delighted to be in collaboration with several industry experts. Our mentors offered to be part of Fuse because of a strong sense of synergy, a shared vision, and faith in a collaboration that aims to bring meaningful assistance to the selected artist and truly help them to accomplish their dream. Blow Photo and all of our Partners are offering their resources to make Fuse a high-quality production.

A creative multimedia art space in the heart of Dublin city, D-Light is an important member of the art community in Europe and a beacon of creativity and support for artists in Dublin and further afield.

Founded in 2010 Blow Photo was created to promote and support photography through publications, talks, workshops, exhibitions and education events. Over the years Blow Photo have been discovering and sharing fine art photography in Blow Photo magazine publication. Blow has published 17 issues, showcasing almost 300 photographers, exhibited Irish work at the European month of photography in Berlin, collaborated with southeast museum of photography in Florida and most recently with Hamburg Trienniale.