Max Pinckers

©

©

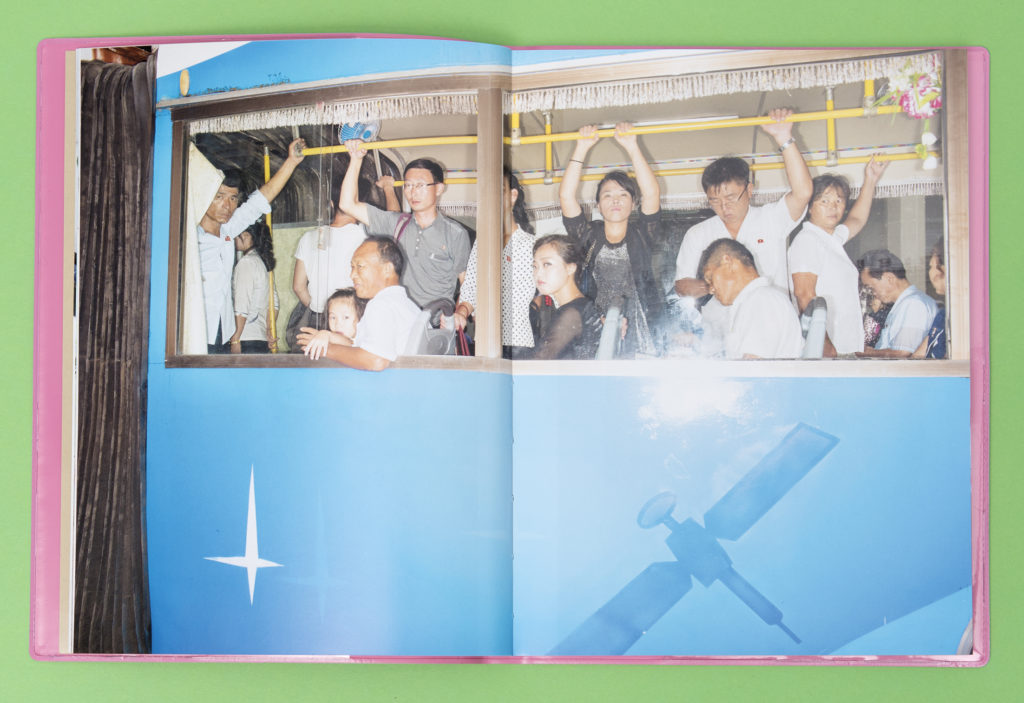

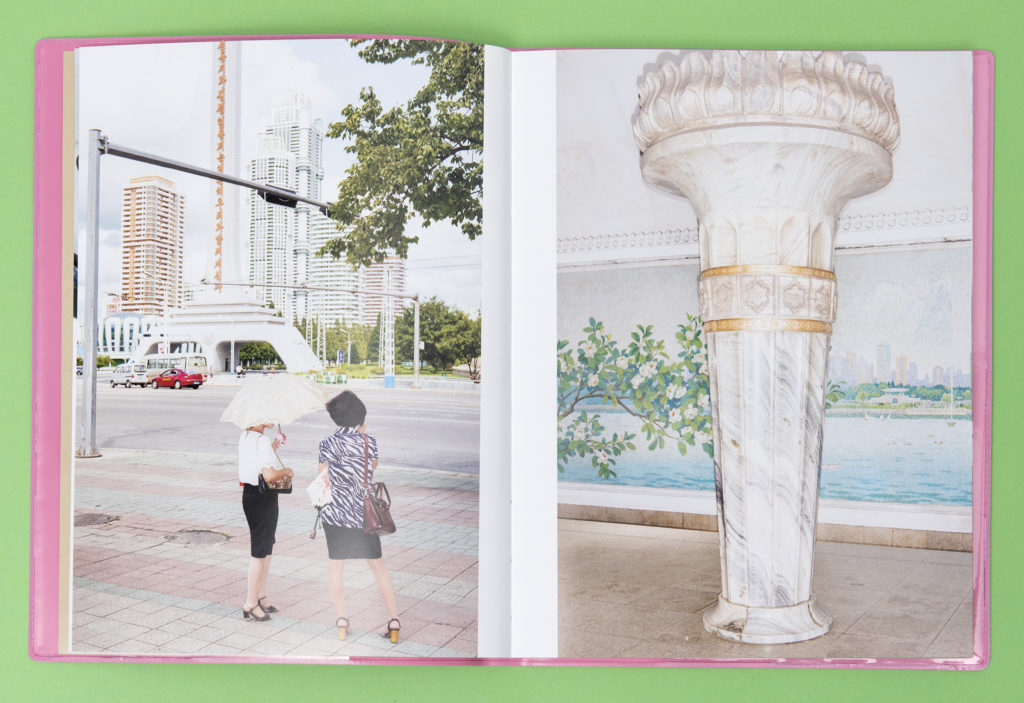

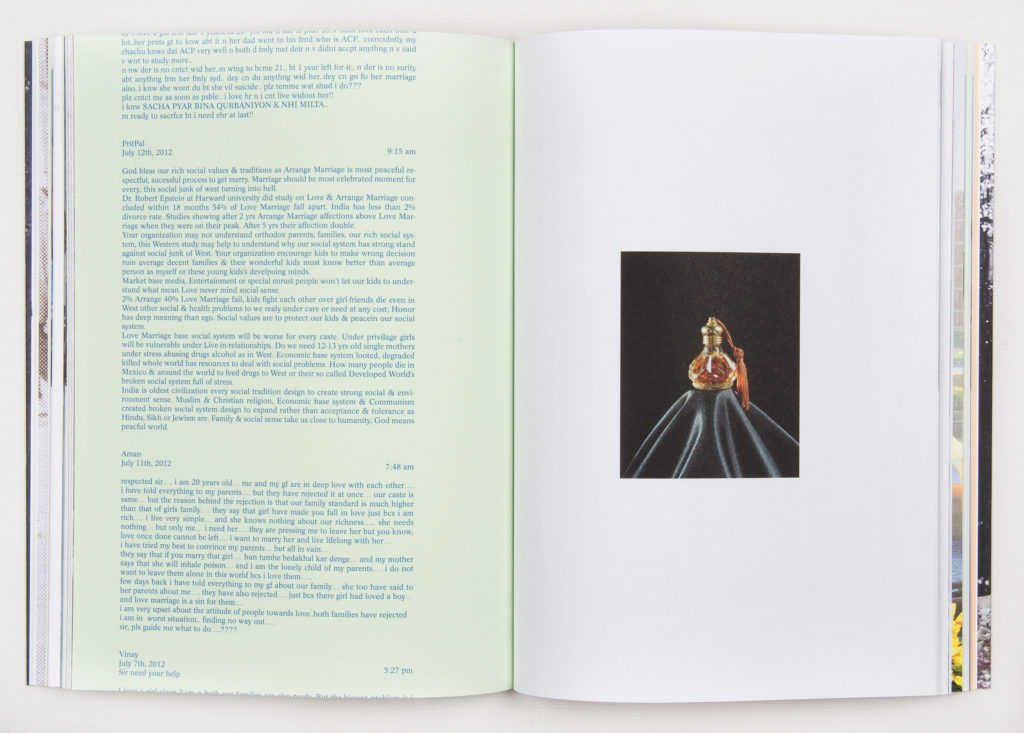

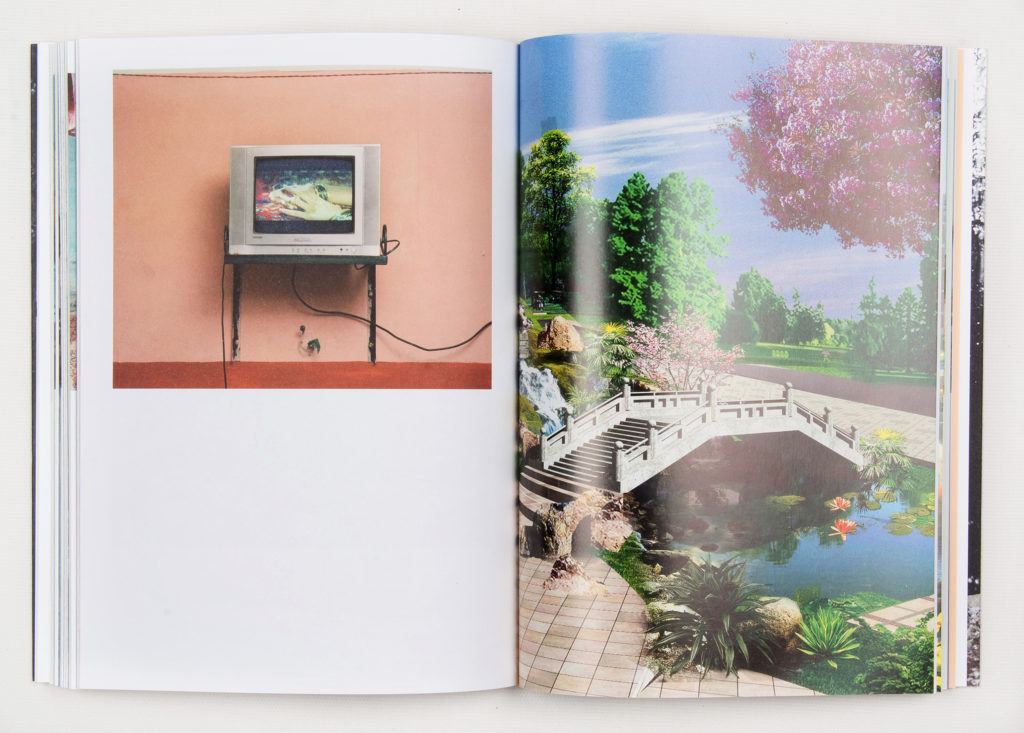

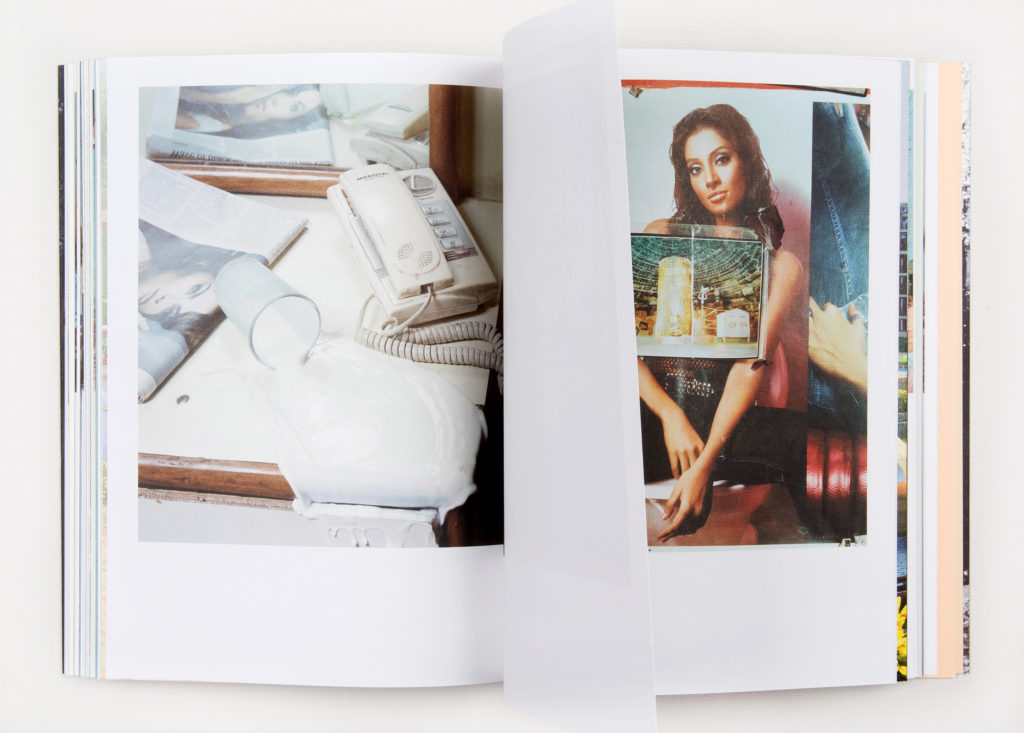

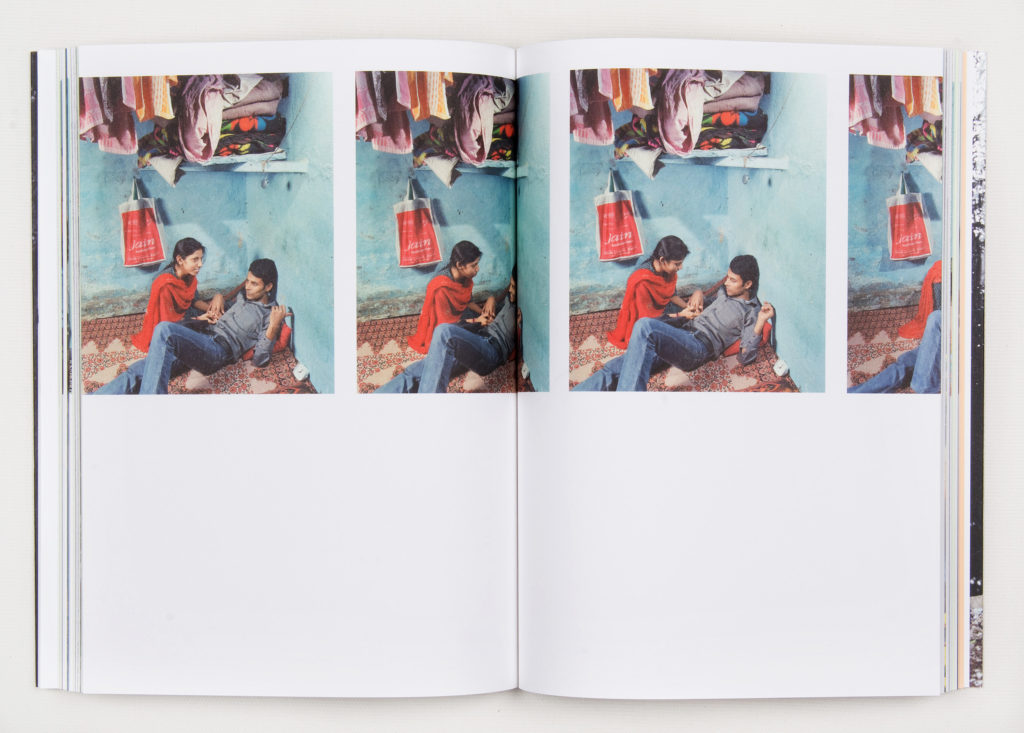

Max Pinckers is a Belgian photographer. He has self-published his books The Fourth Wall (2012) and Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty (2014), Lotus (2016), and Margins of excess and Red Ink, both released in 2018. He founded his publishing house, Lyre Press, in 2015. He won international awards, including the M. Hans Vossen Prize, a Photographic Museum of Humanity grant, the Edward Steichen Award Laureate and the Leica Oskar Barnack Award.

http://www.maxpinckers.be

HOW DID YOU START OUT?

My first book, Lotus, was made in 2011 as a collaboration with another photographer, Quinten De Bruyn. I was still a student at the Academy, in my bachelor year. We made a kind of a Dummy and printed 40 copies.

Quintin and I wanted to explore the aesthetics applied in documentary photography. We wanted to over-aestheticise documentary pictures and explore the subject of transgender women in Thailand, also known as ladyboys.

We combined our photographs with photographs the ladyboys themselves took, which were very amateuristic, and brought the two types of aesthetics together.

WHY A BOOK?

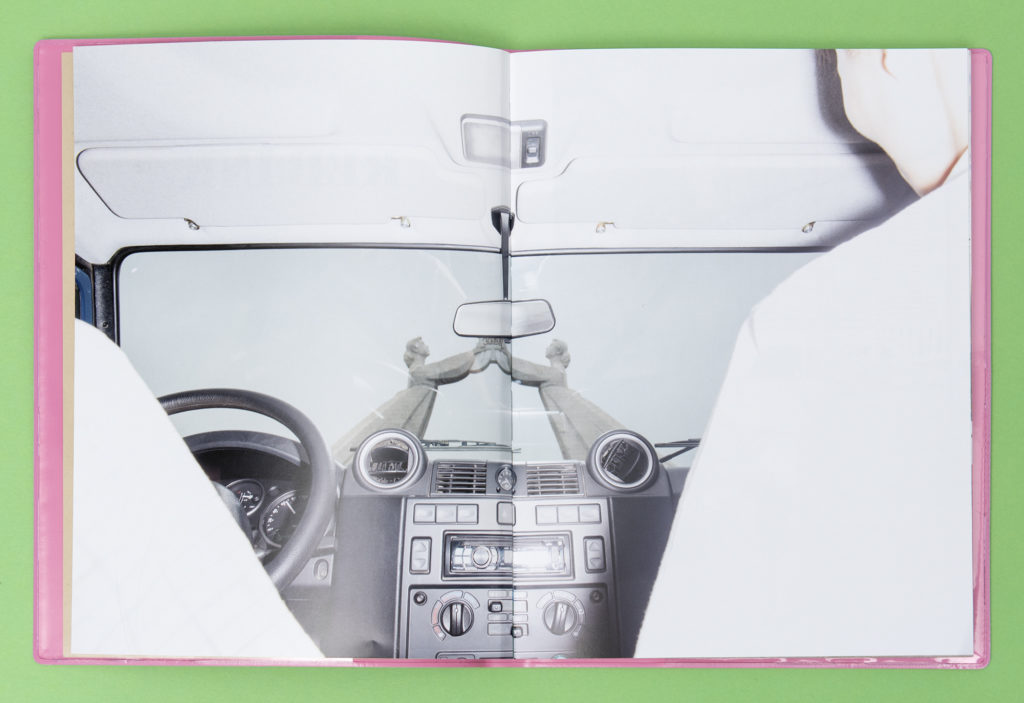

Working on the project, we already knew we wanted to make a book, because it’s a way to create a kind of narrative. I don’t like to use the word narrative so much because it becomes a kind of anti-term, but it’s a way that you can

build up a series of images compiled at the same time. With a book it’s final, everything is there, but you can also bring two disparate registers together. So, for example, we hid the ladyboys’ own pictures behind flaps in the book, so that you first see only the photographers’ point of view and then you get to reveal another aesthetic, another way to approach the book.

Books allows this way of working. I didn’t have any experience of making books, so we really had to learn as we went along. We didn’t completely know what we were doing back then.

HOW DID YOU GO ABOUT GETTING IT PRINTED?

I sent an email to all the people I knew appreciated my work. I said ‘I’m making a dummy book, but I need money to print it because it’s still expensive.’ Then I thought, instead of printing five copies, why don’t I just ask everybody who would like a copy to pay up front? So it was kind of pre-ordering, but in a way that the book couldn’t be distributed. It was quite expensive. A book cost €60 or something because it was digitally printed in a very small run, about 40 copies. Everybody just paid the price of the production, then got a book.

We didn’t made any profits. We produced maybe 10 copies for ourselves and the everybody else got a book.

So that was it, very basic. Our plan was to send the 10 copies that we had to publishers and ask if anybody was interested. I did contact some people, maybe I didn’t put enough effort into it, but at a certain moment, I hadn’t got any response, nobody was really interested, so we kind of put it on the shelf and thought ok, maybe one day we can publish it.

One year later, when I made my second book, The Fourth Wall, I self-published and printed 1,000 copies. Lotus stayed on the shelf until 2016 and then I remade that book in a bigger edition.

HAD YOU CONSIDERED CROWDFUNDING?

When we did Lotus, crowdfunding didn’t yet exist. We did crowdfund for The Fourth Wall, which was was also a practical consideration: the whole book is designed to be printed on newspaper, but the Dummy couldn’t be printed on newspaper because you need a minimum of a 1,000 books to even turn on the offset machine. So the Dummy was on normal paper, which was a bit weird because the design was adapted to newsprint. So because it had to be on newspaper print, I had to make 1,000 books, so I had to crowdfund the money I needed.

I had no distribution plan whatsoever, so when the book was printed, maybe 150 or 200 books were sold on the crowdfunding platform, but I had 800 books in my living room that had to be distributed.

HOW DID YOU COME TO THE ATTENTION OF MARTIN PARR?

First thing I did was send a copy to all my favourite photographers and curators and people who interest me in the art world. Little by little, I started getting emails from online bookstores. People started asking if they could write about the book. Step by step, I learned the process. And then I had a break-through moment.

Martin Parr chose The Fourth Wall as one of his best books of the year and put it on a list. I was not so familiar with these lists, but all of a sudden, the next day, most of the books were distributed. I got so much exposure out of nowhere, and that really lifted interest in the work.

SO THAT KEPT YOU GOING?

I’m now on my fifth book. I work together with my wife. We deal with the distribution and we built up our own system, our own way of sending the books. We work with a lot of very loyal people who support us, who always buy our books. Self-publishing has really become part of my own practice as an artist, it has become part of the work and I really enjoy that. That doesn’t mean that I’ll never publish with a publisher. I would of course be interested in doing it.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN USING A PUBLISHER AND SELF- PUBLISHING?

The main problem in self-publishing is the distribution, because you can’t only go so far. I’m sure there are publishers that you can work with and be free to do what you wanna do, who trust you, where there is a mutual trust.

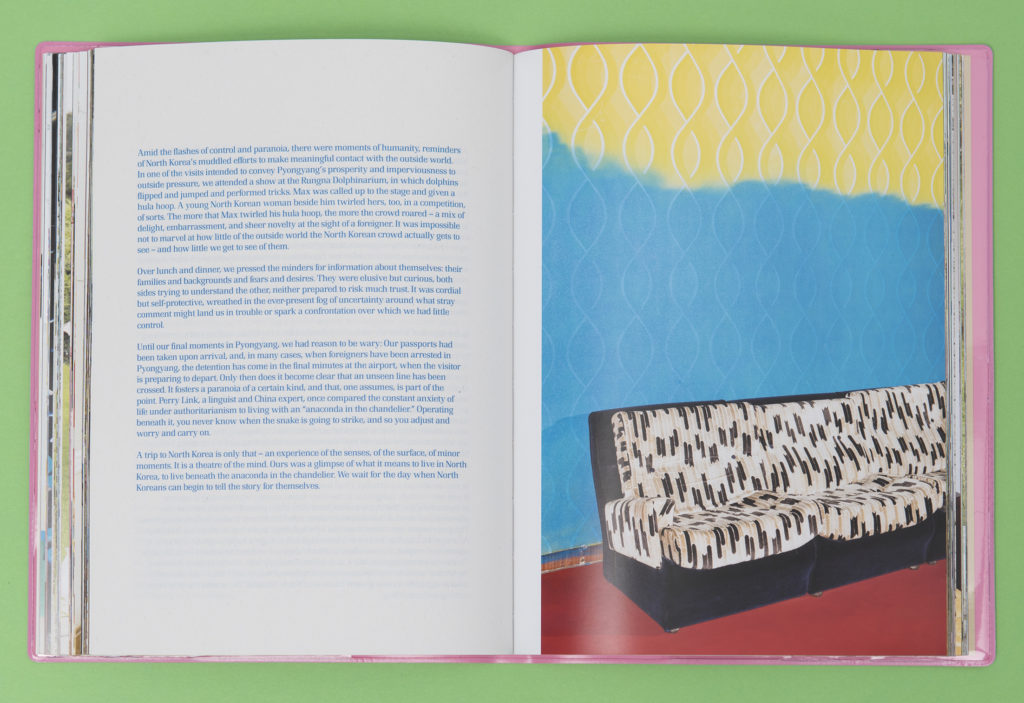

For the last book [Margins of Excess], our print run was 15,000 books. Red Ink was 8,500. Those are the same kind of run sizes that a big publisher would do, and we can distribute the same amount of books a bigger publisher would. But, of course, a publisher has a distribution network that can ensure your book is in every museum store around the world and that every book store stocks it. In self-publishing, you’re limited to very specialised places. So, if I work with a big publisher, I would be interested in doing a very high print run and getting it out as far as possible, so that it reaches a public that I cannot reach myself.

HAVE YOU BEEN APPROACHED BY PUBLISHERS?

Yes, and the deal they offered me wasn’t financially interesting. It’s a very tricky business. If you publish a book with a big publisher, most of the time, it’s at the same time as a big exhibition in a museum or something like that, or you have partners that pay for the production of the book, or some kind of collaboration between different publishers that carry the cost and so on. When I was approached, there was no partnership with anything else, it was just one to one. Then the construction gets very tricky financially. It’s never been the case where I say, ‘Hum, that’s something I couldn’t do myself.’ I’ve always thought ‘Can I do it myself and stick with my own agenda?’

SO YOU TAKE A PUNK ROCK, DIY APPROACH?

Exactly! And that’s the only way you get to know how it works. A lot of people ask me, ‘Should I self-publish?’ I say go for it, but it’s a lot of work. You have to learn step by step, how it works from talking to people, getting the business side of it, dealing with the percentages and commissions.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED FROM MISTAKES?

One of the really difficult things is the number of copies. So we’ve overshot, we made a book with way too many copies. There are books that we made too few copies of, that sold out so quickly they never were even seen at books fairs. And, when you start making pre-sales of the book, a lot of the books are already gone before the distribution.

Timing is another lesson: when you release a book it has to coincide with festivals or exhibitions. These are things that I learned as I went along.

HOW DID YOU LEARN ABOUT PRICES AND PAPER SIZES?

Pricing and paper are also something you learn as you go along. After making a couple of books, or collaborating with designers, or having a close relationship with the printers that make the book or the binders, you realise that there are ways to economise on production prices.

For example, if you use a certain size of paper, it exactly fits an offset sheet, which is 70x100cm, and you can use that one sheet to maximum efficiency. If you go one centimetre bigger you might only use half of the sheet, and the price of the book doubles. All these little tricks! So when you’re making a book, you’re thinking, ‘Maybe we should use this size or that size, or maybe we shouldn’t. Should we go for a unique size, at greater expensive? Can can economise on some other choice?’ That’s all a part of the process, and it’s part of working with the designer. Until now, we’ve never had to make a compromise. It’s always been exactly what we wanted it to be.

WOULD YOU CREATE THE SAME BOOK TODAY AS YOU DID THEN?

Probably it would be different. But I also like that it’s been done this way, and that it’s kind of part of that time and artistic process. It has its place.

CAN YOU SPEAK ABOUT THE PROS AND CONS OF THE INDEPENDENT SCENE?

Here on the boat (Polycopies, Paris, November 2018 ),

everybody knows each other, everybody’s friends, everybody supports each other. That’s a beautiful part of the—I don’t want to use the term ‘underground publishing scene’ but it does pose an alternative to the mainstream, more popular work that is out there at Paris Photo. The most beautiful things are here.

The downside is that it can be a bubble, a kind of hermetic environment where sometimes I feel it’s a bit too disconnected from the things that happen outside. It also creates a space for a lot of things to be created, and not everything might be good. But that’s not bad: the more things are made the better, so fantastic things comes out. But, on the other hand, when you go to a fair you can’t differentiate anymore between all the things that are being published. One of the roles of a publisher is to curate: what is a good work, what should be published and what shouldn’t. So you could say the critique [of the independent scene] is that everybody gets free rein.

IS THERE A RECIPE FOR A GOOD BOOK?

No, there is no recipe. For me, a good book is a book that translates the concept of the work in the best possible way. It’s not a particular form, it depends on what the artist wants to say, on what the works want to say. If the book complements the concept or the intention, then it’s a good book.

ANY WORDS OF ADVICE TO THE ARTIST MAKING THEIR FIRST BOOK?

I’m very happy myself with how the process went so I don’t have so much. Maybe be extremely critical about the choices you make, take your time, think about what you

do, reflect on the world and always make sure that your own intentions and your own work is given the utmost respect. Make sure it’s done in a way that you want to work. Create some kind of independence for yourself and stick with that, and be very critical about the conditions in which you work, about how you work. Of course talk with as many people as possible, make as many relationships as possible and try to get your work out there, that’s the most important thing.

interview by Carine Dolek